The bestselling author on how a trip to Cape Town inspired her fascinating historical fiction novel.

A few years back on holiday in South Africa I had dinner in the lovely restaurant Catharina’s, which forms part of the Steenberg wine estate in Constantia, Cape Town. The restaurant was named after Catharina Ras, the first owner of the estate. In September 2019 the restaurant underwent a major revamp and reopened as Tryn, the contraction of her name by which Catharina was more familiarly known.

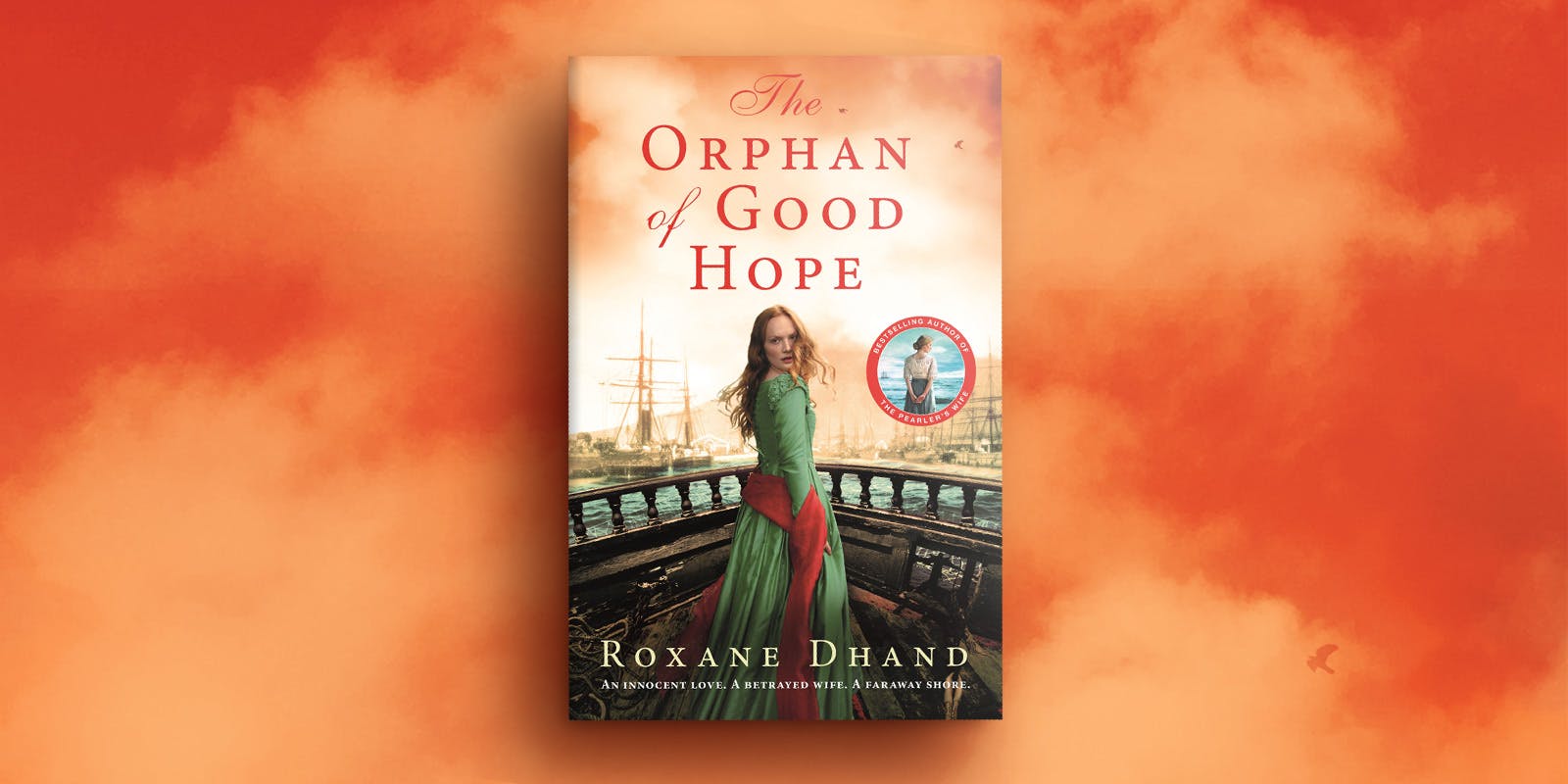

Her fascinating story was printed on the back of the menu and as I read it I saw the earliest outline of my character Johanna in my novel, The Orphan of Good Hope.

Born in Lübeck Germany, Catharina Ustings was to become one of the most venturesome and controversial figures ever to settle at the Cape. It is said that after she was widowed at just twenty-two years old, she stowed away on a ship, dressed as a man and sailed into the Cape, just ten years after the first Cape Commander Jan van Riebeeck landed there in 1657.

Looking further into her story, however, I discovered that she sailed on the Hoff van Zealandt from Wielingen on 27 January 1662, en route to de Caep de Goede Hoop where it dropped anchor on 25 July 1662. It is assumed that she travelled as a widow, but I could find no evidence to support this. It would seem more likely that she set off on her journey with her husband in search of a better life and that he died from scurvy during the voyage.

In the mid-seventeenth century, the Cape was a wild, uncivilised place; its laws similarly so. A woman on her own would have faced a precarious future with no man to protect her. Within a few months of her arrival, Catharina had found husband number two.

On 3 September 1662, Catharina married Hans Raas, a soldier and freeburgher. On their wedding day, travelling from Table Bay to Hans’s farm on the Liesbeeck River at Rondebosch, Hans survived a knifing incident. He was killed and eaten by a lion a few years later. Legend would have us believe that Catharina jumped on her horse, rode it astride like a man, tracked the lion down and shot it with her musket. Whether the story is true or not, it gives us some insight into her unshakeable spirit, which led her to marry five times and provided the inspiration for my character Johanna. Elements from her story have found their way into the book.

By the time she had buried husband number four, Catharina had learned that marriage could not be relied on as a source of security and set her sights on owning land herself. (It is unclear why she chose to retain the name of her first husband at the Cape.)

That she was starving is without question. Widowed once more, with her nearest neighbour four hours away, she had to fend for herself and her eight children. Documents tell us that Catharina was in receipt of a monthly rice ration from the Dutch East India Company for settlers unable to provide for themselves.

It is all the more remarkable therefore, in an era when women had no legal rights, that Catharina pioneered land ownership in South Africa. In 1682 she approached Simon van der Stel, the Cape’s first Governor, and requested twenty-five morgen of land at the foot of the Steenberg Mountain.

It is rumoured that they were romantically involved, but whether they were or not, he granted her request, and presented this land to her as a gift. She called it Swaaneweide – The Feeding Place of Swans – which I used as the working title for my book.

She later approached the visiting Dutch Commissioner, on his annual visit of inspection, for a legal title deed for her land, which he granted in 1688. The title deed, which today is displayed in the original Manor House of the Steenberg Hotel, granted her a mandate ‘to cultivate, to plough, to sow and also to possess the farm below the stone mountain’.

Catharina’s story gave me the bare bones of a book, but I needed more to flesh out my novel. I decided to explore the administration at the Cape of Good Hope at this time in history.

My research took me to Amsterdam, from where the Dutch East India Company – also known as the VOC, the most powerful trading company of the era – administered the Cape in the seventeenth and eighteen centuries, until British forces landed in 1795 and claimed it for King George III.

While researching the Dutch East India Company at the Amsterdam City Archives, I came across a ledger of orphans who had worked for the company. The register formed part of the records of the Burgerweeshuis – the Citizens’ Orphanage – which only accepted orphaned children from Amsterdam citizens and relied on funds held in trust or sponsorship to pay for the children's board and lodging. The original building still stands and now houses the Amsterdam Museum, a section of which is dedicated to the former use of the building.

The male orphans were apprenticed to a guild to learn a trade, such as cooping (barrel making) or carpentry, and were then able to find employment with the VOC. It is still possible to see the glass-fronted lockers where the boys kept the tools of their trades, and I have used these lockers as the backdrop to a scene in the Amsterdam section of the book.

The female orphans were trained in skills that would eventually equip them to seek self-supporting employment – more often than not as domestic maids. Whether or not they ever scrubbed the aforementioned lockers is purely an invention on my part.

At the time my story is set, Simon van der Stel had written to the Lords Seventeen in Holland asking for marriage maids to be found from the orphanages in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. He was concerned at the ratio of men to women in the nascent colony and was anxious to secure a more balanced pattern of the population as well as an increase in family life.

Of the 48 girls requested to sail to the Cape to marry free burghers, only eight young women from the Orphan Chamber at Rotterdam were among the passengers on the ship China, which sailed from Rotterdam on 20 March 1688.

For the purpose of my story I have taken liberties with this fact and have placed the orphans in the orphanage at Amsterdam although their number and circumstances are identical.

It is true that the Dutch East India Company needed cheap labour to populate its sailing fleets that facilitated trade with the East. It is also possible to link the Burgerweeshuis orphanage with the Dutch East India Company through a journal – which still exists – entitled Book of Orphans Who Went to the East Indies.

Within the journal's pages of scrupulously kept records it is possible to see the name of the boy, the ship he sailed on, the job he was employed to do, and his fate. Any money he was owed in back payment was brought into the orphanage’s account. A random entry, by way of illustration:

Pieter Mathijsz Sparmont from Amsterdam went to the East Indies on de Ridderschap in 1686 as a ship’s boy. Missing since the end of August 1692 in Batavia [now Jakarta, Indonesia]. 1701 still missing. In January 1705 still missing, but his estate worth 131 guilders 4 stuivers and 15 pennies brought into the orphanage’s account.

It didn’t take much further inspection to see that often children who sailed to the East Indies died in the service of the Dutch East India Company, but their unclaimed wages returned to the orphanage in Amsterdam. Whilst this is not conclusive proof that the Dutch East India Company and the Burgerweeshuis in Amsterdam were involved in a mutually profitable arrangement, there were enough similar entries to suggest a plotline for my novel.