Ayik Chut Deng reveals how a child’s curiosity became a lifelong burden.

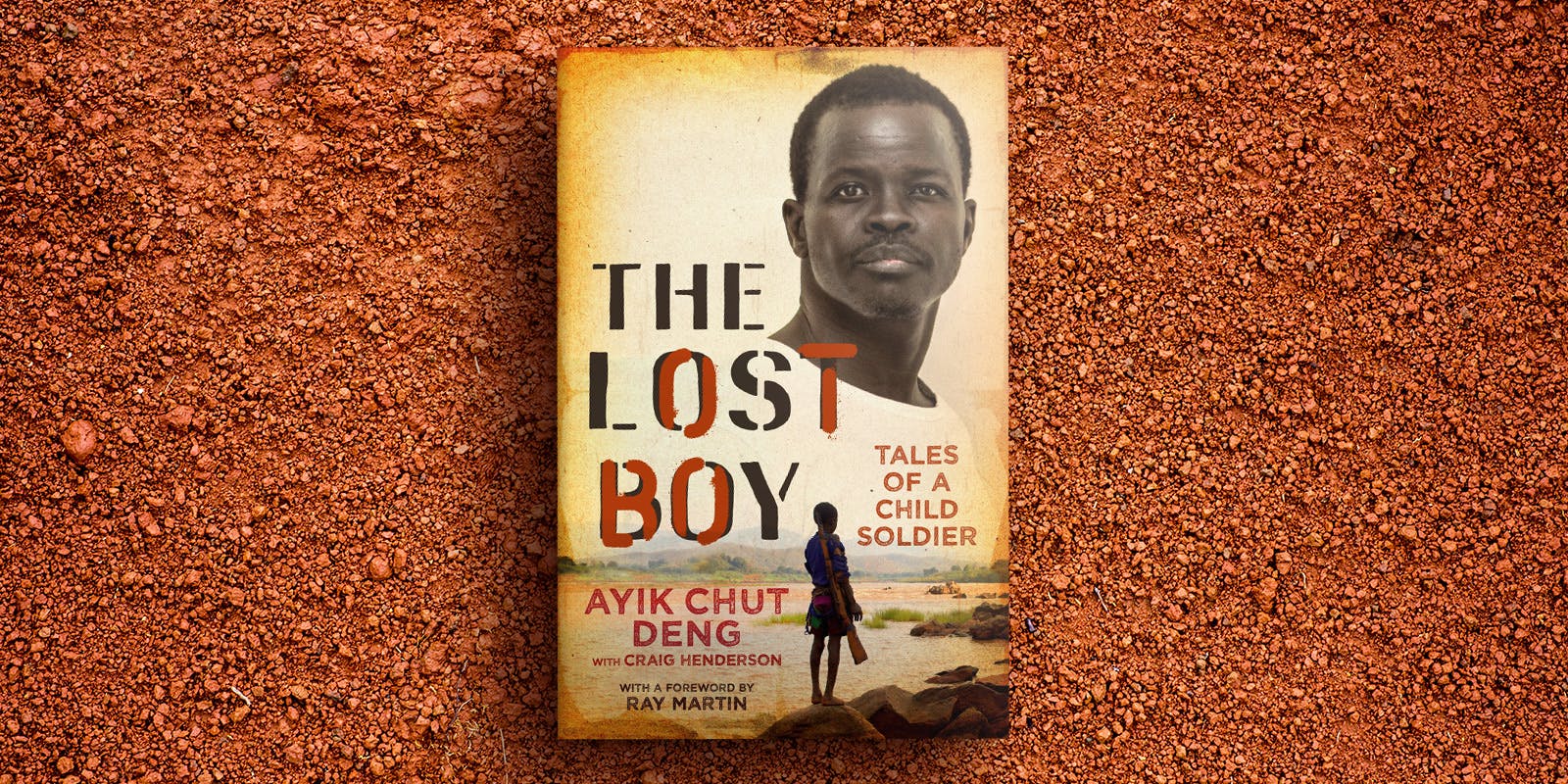

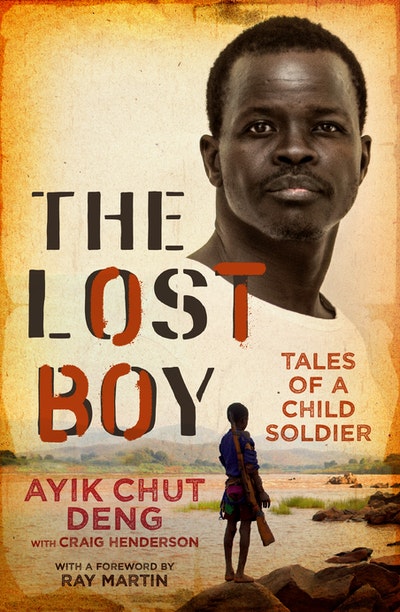

Ayik Chut Deng’s memoir, The Lost Boy, is a harrowing account of the complexities of trauma, and one man’s story of how he got to where he is today. As a child soldier in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, Deng was exposed to unthinkable violence and torture. Then, at nineteen years old, he and his family escaped the bloodshed of the Second Sudanese Civil War to resettle in small-town Queensland.

Deng struggled to adjust to life in the ‘lucky country’. Suffering Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, he grappled with multiple mental health issues and struggled with alcohol and drugs – ultimately resulting in a self-destructive downward spiral towards oblivion. It took him many years to emerge from the shadow of the trauma he’d experienced, and now he has shown enormous courage to face past demons in the retelling of his extraordinary story. In the passage from The Lost Boy below, Deng reveals his initial attraction to the soldier’s life, and an event which stirred rage in his young heart and mind.

The first time I saw an AK-47 assault rifle I just knew I had to have one. It was 1984 and the gun in question was cradled in the wiry arms of a young soldier who’d arrived in our village. Months earlier, strange mobs of people had started flooding through Twic on foot in ever-increasing numbers. They couldn’t speak Dinka and I couldn’t understand a word they were saying, either. These travellers would stay overnight before leaving in the morning, always heading east.

‘There is a war coming so these people are going to Ethiopia,’ one of the tribal elders explained to me. ‘Some are going there to be safe from the fighting, but the men are going to Ethiopia to get trained so they can come back and fight the Arab raiders.’

As usual, Mum had read the danger signs long before I knew anything was wrong. Over the previous months she’d noticed a slow, steady exodus of young men from the villages. These guys were meant to be the protectors of the community, the teachers and providers who guided the little ones, so when they all left to join the SPLA, Mum’s heart filled with dread. When her oldest son – my big brother, Aleer – answered the rebel call too, the war really started to crash in on our family.

By 1984 the SPLA was going to villages throughout the south to tell the tribal chiefs that men in their late teens and twenties were needed as recruits. It wasn’t a blanket edict or outright conscription – if a family had only one son he wouldn’t be required to join, he could stay in the village and help care for his loved ones. But if a family had three or four sons? The oldest would be told to serve in the SPLA. Like a lot of the early rebel soldiers, however, my brother Aleer didn’t need to be asked to fight for South Sudanese freedom – he eagerly volunteered.

Aleer had remained in Juba to study at university after our father died and the day he suddenly appeared in the village was one of the happiest of my short life. I’d been jumping up and down with excitement at seeing him, only to feel shattered a few days later when he joined a caravan of young men heading east towards an uncertain future. I watched Aleer leave, walking further and further away across the baking hot ground until shimmering wisps of heat mirage wrapped around him and pulled him from view. I was so heartbroken to lose Aleer again that I wept for two days straight. I didn’t know it was the last time I would ever see him.

Many months later, word reached us that Aleer had been killed before he even made it to the SPLA training base in Ethiopia. Witnesses relayed the story to our elders. Because Aleer was an educated man, he had been placed in a leadership position even before he underwent formal training. As his group of recruits embarked on the months-long walk from Twic to the border with Ethiopia, Aleer and a couple of others were handed AK-47s and ammunition and told, ‘You’re in charge. You’re responsible for the rest of these people.’

Late one night as the group was travelling through a tribal area, one of the other temporary leaders got drunk and started firing rounds into the air.

‘Stop it!’ Aleer told him. ‘There are people sleeping here, children sleeping. These are our people!’

But apparently the drunk guy couldn’t help himself, perhaps also drunk on the power an assault rifle brings. He resumed his midnight machine-gunning so Aleer snatched the weapon from him. ‘You don’t listen, man,’ he told the rogue. ‘I’m keeping your gun until we get where we’re going or until you can stop behaving like an idiot.’

After travelling for a few more hours, Aleer felt the troublemaker had sobered up and calmed down so he handed the gun back. The group continued walking but the guy just re-loaded the AK-47 and shot Aleer in the back of the head.

Today I find it hard to visualise Aleer’s face and when I do think of him it is as a small, blurred shape on a far and dusty horizon. The bitter memory always makes me cry.