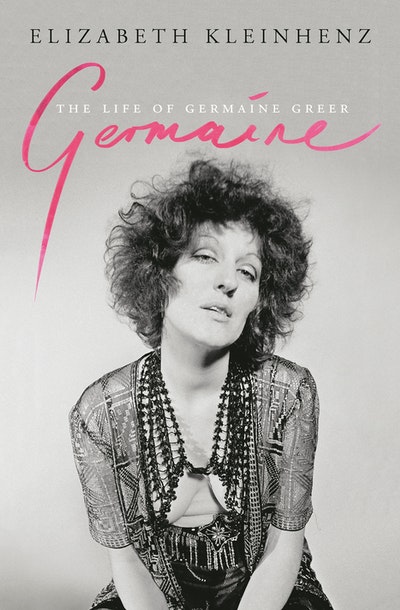

Elizabeth Kleinhenz on the mammoth task of tackling 487 archive boxes.

Germaine Greer sold her archive to the University of Melbourne in 2013. I started my research for a biography of Greer in mid-2015 and completed the biography in March 2018.

My original plan was to organise the research chapter-by-chapter, working directly from the Greer archive. The first problem I encountered was the sheer volume of the archive itself – 487 archive boxes, each box containing varying numbers of folders, which took up 82 metres of storage space in the university’s depository. The archive is arranged in designated ‘series’ – ‘correspondence’, ‘print’, etc. I started with the ‘correspondence’ series, but because the letters were not arranged chronologically, I was finding it hard to get a handle on anything.

At some point I started to just potter around – reading the correspondence, taking notes of anything interesting and letting it all flow, hoping that it would all come together, somehow.

Then in March 2016, I received an email from the university telling me that they were closing the Greer archive to all researchers until at least the end of the year. A curator had been appointed and she and her team were about to start the massive task of curating.

At first I was appalled by this news. I realised that would I have to change tack – to concentrate my efforts on other avenues of research. So I worked solidly on teeing up interviews with people who knew Germaine, or knew a lot about her; I read or re-read her books and other works by her, starting with The Female Eunuch. I trawled the internet, including YouTube, and found a plethora of information – books, newspaper and magazine articles by and about her.

In gathering this information I realized that I was setting up a useful framework of background information for the archival material. As it turned out, this proved to be a much more workable way of proceeding than my original plan.

But there were still hurdles – the first was the subject herself. When I first got the idea to write about her, I had no idea how much she hated the thought of anyone writing her biography. I was well into my project before I met Christine Wallace who wrote the first and, until now, the only Greer biography. I discovered how nastily Greer had reacted to the publication of that book, and the extent of the hurtful personal attacks she had made on Wallace. Did I really want to expose myself to this? More importantly, was there an ethical problem in going ahead in the face of Greer’s opposition? Did she have a point? Isn’t there something uncomfortable about having one’s life exposed for all to see?

I got over this ethical question after reflection on two facts: first, there is no way Germaine Greer can be described as a private person. She has made no secret of the details of her life – her gynaecological problems, her dislike of her mother, every opinion she has ever had – are out there in the public domain. She could not have sold her huge archive without realising that writers and researchers like me would use it for biographical purposes.

Second, I believed that my work was important. Germaine Greer is probably the most prominent and influential Australian woman of the 20th and early 21st centuries. Casting around as part of the research, I discovered that many people see her as a kind of caricature: ‘a pain in the neck’, ‘an attention getter’ and, ‘a ratbag’ were some of the epithets used to describe her. She is so much more than this: she is academically brilliant, perceptive, powerful, quite possibly a genius, as her colleagues Fay Weldon and Carmen Callil described her to me. She deserves to have the record set straight, and she deserves to be awarded her proper place in Australian history and culture.

I have had two letters from Germaine Greer. The first, an email, was in response to a polite request I made about how she saw her archive being used by researchers. Her response can best be described as uncivil. The university owned her archive now, she wrote, curtly. Let them decide what should be done with it. And why had I failed to get her title right? She was ‘Professor’, not ‘Dr’. Her second letter was sent in hard copy, on nice, thick paper. It was more of the same. She addressed me as ‘Mrs Kleinhenz’. (I didn’t mind her forgetting I had a PhD, but as a feminist, I haven’t been ‘Mrs’ for at least forty years! Tell me she wouldn’t have known that.)

I would advise anyone about to embark on a task similar to this one to become familiar with the relevant sections of a university’s online resources. The team at the University of Melbourne who curated the Germaine Greer archive developed some excellent supports, in particular a tool called ‘Finding Aids’ that made locating the material much more manageable.

I found it helpful to gather and record the researched information chapter-by-chapter, then to write the chapter. Of course, this took a lot of revision and rewriting all the way through and at the end, to achieve a coherent whole.

In hindsight, I would have started – as I was eventually forced to do by the temporary closing of the archive – by using secondary sources to map out an overall framework for the biography. (This may not work for all subjects, but it certainly worked in this case.) And I would not have started on the archive itself without using the online help provided to navigate the huge volume of material.

I would also be more meticulous about noting the details of all the references dates, page numbers etc. as I found them. This would have saved a lot of tedious checking and modification at the end.