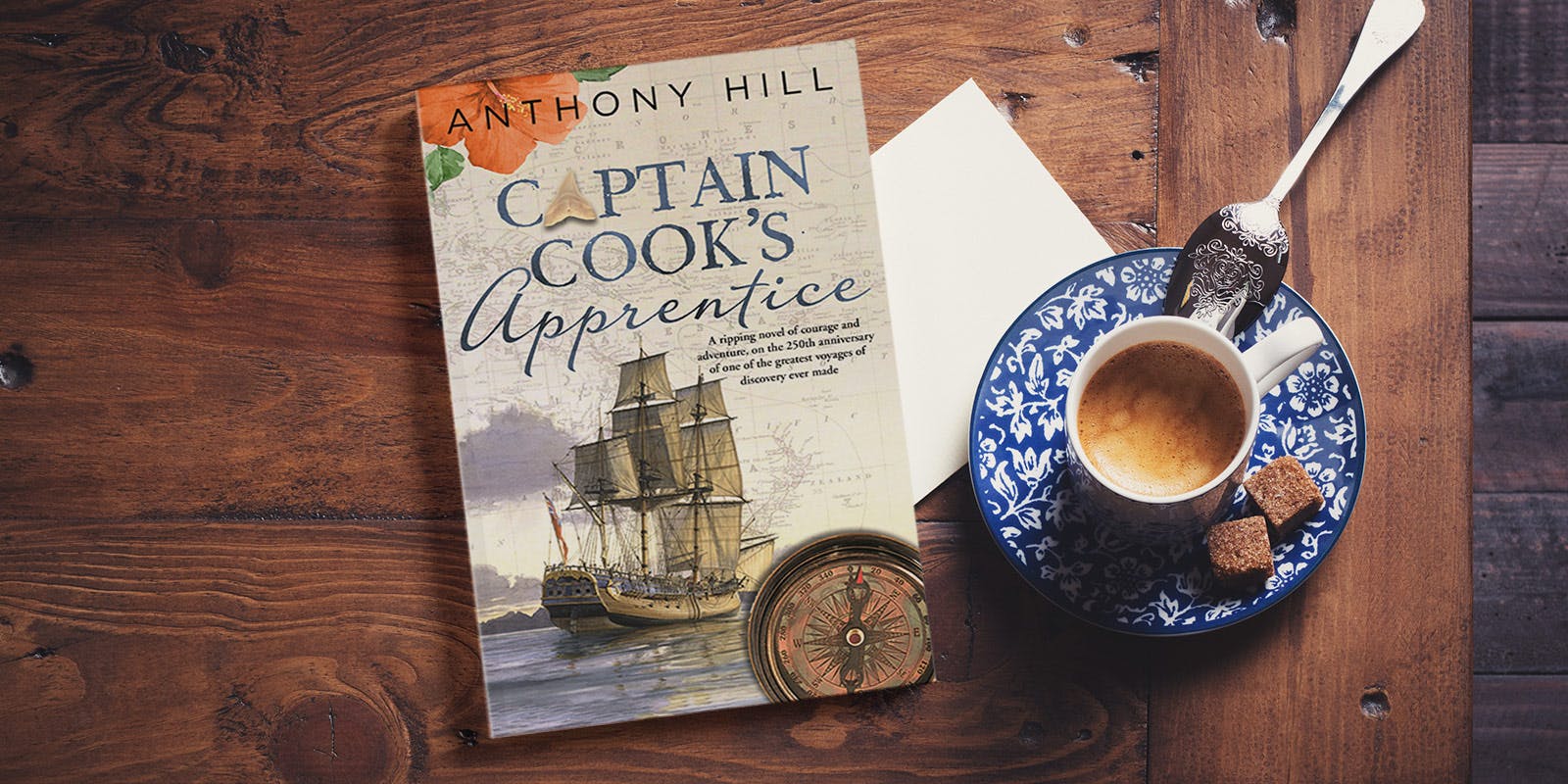

The author of Captain Cook's Apprentice reveals some of the new words and ideas collected by the voyagers on HM Bark Endeavour almost 250 years ago.

26 August 2018 marks the 250th anniversary of HM Bark Endeavour leaving England under Lieutenant James Cook on one of the most important voyages of discovery ever made.

When the ship returned three years later, it brought back the first charts of New Zealand and the east coast of Australia, opening them to future British settlement, and over 50,000 specimens of plants, animals and human artefacts many of them quite unknown to European science.

Also among its cargo were many new words and ideas – common enough today – that were heard on English tongues for the first time.

Tattoos, for instance, were first described by Captain Cook on Tahiti. The botanist, Joseph Banks, and the artist, Sydney Parkinson, both had a small, intricate pattern painfully tattooed into their flesh with the sharpened teeth of a bone tool dipped into a purplish-blue dye - but they were nothing compared to the elaborate spirals and arches decorating the faces of the Maori they met in New Zealand.

For many decades afterwards, tattoos were largely confined to seamen and travellers generally to show they’d been to the South Seas: now, they’ve become the fashion statement of a whole generation, and there’s barely a suburban shopping strip that doesn’t boast a tattoo parlour.

Surfing was something else first described for Europeans by Joseph Banks in Tahiti, when he saw boys riding the prows of old canoes on the great Pacific waves that broke upon the reef and carried them all the way to shore. Today, of course, the sport is a way of life for young people the world over, not least in Australia.

Taboo is another word brought back by the Endeavour men. The idea that some things are too sacred – or dangerous – to be approached, is ancient enough. But on Tahiti it seemed carried to extremes. Stones from their sacred sites - their marae - couldn’t be moved, or leaves picked from plants growing nearby. And a young chieftain had to be carried everywhere in public, because if his feet touched the ground it immediately became taboo and nobody else could walk on it.

A Tahitian priest, Tupaia, sailed with Endeavour when it left the islands. On reaching New Zealand they found the language almost identical, for the Maori had sailed from the Polynesian homeland centuries before in their great double canoes or waka, a word still used by specialists – as are the names of many of their fearsome weapons, such as the greenstone or carved bone clubs known as patu.

But the words spoken by the Aborigines of the east coast of Australia were ancient and unknown to anyone on board the ship. The only prolonged contact between them was at Endeavour River, as Cook called it, in far North Queensland, where he stayed for two months to repair his vessel after it was nearly wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef.

Banks and Parkinson both made lists of words used by the Guugu Yimithirr people to describe the everyday things of life ... including that extraordinary beast the Endeavour men saw looking like a greyhound that hopped and called, apparently, a gangurru. Kangaroo. They took a skin back to England, where it was painted by George Stubbs, and became the symbol of a whole new nation.

We still use today many of the familiar English names given by Cook to landmarks as day by day the spider lines on his chart enclosed the eastern coast of New Holland. Point Hicks, his first landfall. Pigeon House Mountain. Botany Bay, which he originally called Stingray Harbour because of the sea creatures caught there, but changed to honour the botanists who collected many new plant species unknown in Europe, including the Banksia named after Banks himself.

One new name above all stands out from the Endeavour voyage. When Cook reached the northern tip of Cape York, as he called it, he took possession of the entire east coast of the continent in the name King George. It was the practice of that time, done without any consultation with the local inhabitants.

But what would he call it? New Holland, New Guinea, New Britain had already been taken. New Wales? Perhaps. He wrote it in his Journal, and it remained that for some time. But it didn’t seem quite right. At last he inserted ‘... by the name of New South Wales.’ Much better.

And a new phrase of three simple, everyday words, redolent with their later histories, entered the language.