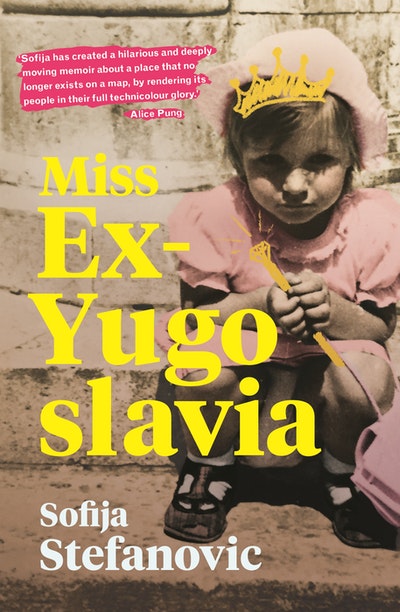

Sofija Stefanovic on her family’s first impressions of the land down under.

Sofija Stefanovic was born into a country destined to collapse. With Yugoslavia on the brink of war, her family was torn between the socialist existence they’d always known and the pull of stability on offer in the distant land of Australia. By turns moving, hilarious and beautifully candid, Miss Ex-Yugoslavia captures the experience of being a perpetual outsider – and learning, in the end, that perhaps you prefer it that way. It is a story about not quite connecting with your old country, while not quite being embraced by your new one.

In this passage from the book, Sofija recalls her first memories of her family’s arrival in Australia:

‘Well, I guess this is it. The arsehole of the world.’

The arsehole of the world was what my mother had been calling Australia, because it was so far from Belgrade and because, to her, Belgrade, bickering populace and economic crisis aside, was the earth’s beating heart. As we got off the plane, she and Branka glanced around for a place to smoke with the desperate eyes of addicts who’d been forced to go cold turkey, with the added torture of babies and preschoolers whining at them. Tullamarine airport was clean and busy, full of locals wearing thongs and big t-shirts, some of them overweight and sunburned, their hair in little braids after holidays in Bali or Thailand. A woman with bare feet walked by and my mother concluded that she must be schizophrenic.

At the luggage carousel, friendly airport officials stood and uttered their greetings: ‘G’day, how ya goin’?’

The Australian accent was formidable to my mother, who had just flown across the earth with a vomiting five-year-old and a cranky newborn attached to her, and was just about ready to eat a cigarette. My mother had learned English at school and used her knowledge of the language mainly for watching the import shows that hadn’t been dubbed and reading academic books she got from the international store. She was now squinting suspiciously at an elderly airport employee wearing shorts and socks to his knees, who called her ‘love’ even though they’d only just met. Was he a sex addict? my mother wondered, sizing up the eager old man. Meanwhile, I had never seen an adult dressed like that. I was fascinated by his exposed elderly legs and his red, scabby nose. I would soon learn that Anglo skin does not take well to the hole in the ozone layer, and I would become accustomed to seeing elderly people with small chunks of skin missing from their noses. The old man pointed toward the exit to indicate there would be no smoking until we were all the way out of the airport.

Finally, we had the bags on a trolley with Natalija strapped to my mother like an angry troll, her hair wild from the static of my mother’s nylon sweater. We crept through customs toward metal double doors that opened automatically, taking us suddenly into the free world or, more specifically, into the giant, bright arrivals hall.

We paused, gathering our bearings. Self-consciously, new arrivals ran their hands over their unbrushed hair, straightened their wrinkled clothes, and wished their breath was fresh and that they could get the smell of aeroplane toilet out of their nostrils. The spectators, on the other hand, were waiting for loved ones – full of anticipation as each person walked out, their faces falling whenever the metal doors spat out a stranger. Feeling those disappointed eyes, the three of us couldn’t do much but keep going along the runway, hoping to spot Dad and scamper to him.

I looked at the waiting faces along the runway – so many more ethnicities than I had seen in Belgrade. Families were waiting with balloons and flowers, toddlers in their best clothes ready to meet grandparents for the first time, people holding signs, crying or laughing, grown men yelling ‘Mama!’ and waving maniacally to little old ladies with heavy European coats. A plane ticket to Australia in the eighties cost a huge amount of money. If a person had come all the way to Melbourne, they meant business.

And then there was my dad at the end of the runway, wearing his old jeans and smiling through his beard. He stepped out from the crowd, squatted down to my height, and opened his arms. The people around me blurred as I ran to him, throwing myself into his loving embrace.

When we walked out of the terminal and said goodbye to Branka and her family, my mother finally got to light her cigarette – all the troubles of the world temporarily leaving her as she exhaled them in a blessed stream of smoke into the unpolluted air.

We looked up at the sky, which extended above us like a vast blue dome. Gone was the small grey sky of Belgrade that hung low like a blanket. Gone were the tall buildings that had surrounded us, the crowded streets and concrete. The sun shone bright above us. This was our introduction to Melbourne winter: 12 degrees and snowless, with a cold, unfamiliar wind.

My dad led us proudly to the second-hand silver Holden Commodore that would be our family car.

‘Look at that tacky stripe!’ my mother said, pointing at the orange trim running along the side.

‘I thought it looked good,’ Dad said, looking again at the orange stripe, which had held so much charm until that second. She rolled her eyes, keeping to herself the nice things she said about him when he wasn’t there. (‘Lola is a genius,’ I’d overheard her saying to friends. ‘Can you believe he rented a car the day he arrived in Australia and drove himself to a job interview? And he got the job straight away, even though he was jetlagged and speaking English!’)

My dad had always made an effort to read English-language novels and magazines, and leading up to the move he’d cranked up his studies, constantly looking up strange spelling rules (‘i before e except after c’) and conversational sayings. He wanted to be the kind of guy who could say A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush and know exactly what it meant, rather than just staring dumbly like a sad immigrant as those around him bantered. He felt empowered that first day as he drove the rented car with the window down toward a job interview in Melbourne’s city, making his way from the sparse suburbs where we would eventually live, through the leafier inner suburbs and to the guts of the big city.

The building where my dad was heading stuck out from the rest, a high-rise towering above high-rises. It was the headquarters of BHP, the multinational mining company that at the time was arming itself with nerds who could automate systems. While Dad’s accent landed him firmly in the ‘wog’ camp, a tech guy with Dad’s accent was regarded as ‘a good bet’ – programmers from Slavic countries had a positive reputation in the world of software engineering. He walked away from the interview that day with a job offer and a salary of $36 000 – about ten times more than he was earning in Belgrade. That afternoon he bought a second-hand Holden Commodore with an orange stripe and went back to the suburbs to find a home to rent for his family.

Our new home was a three-bedroom, low-roofed brick house in a cul-de-sac opposite a small park in McKinnon. The population at the time was around three million, but we were still 16 kilometres from the centre. The sprawl of the city was a shock.

In Belgrade our apartment was considered large, but it was tiny compared with this place. Our backyard in Belgrade was shared by two buildings that backed onto each other, where the resident kids went wild when they came home from school. But now we had a backyard that was just for us, a lonely, large expanse of green grass with a bizarre structure in the middle called a Hills hoist. Dad showed us how it turned, and I imagined swinging from it.

‘That,’ my mother said, ‘is the ugliest thing I’ve seen.’