South Australian illustrator Andrew Joyner describes his inspiration for his authorial debut.

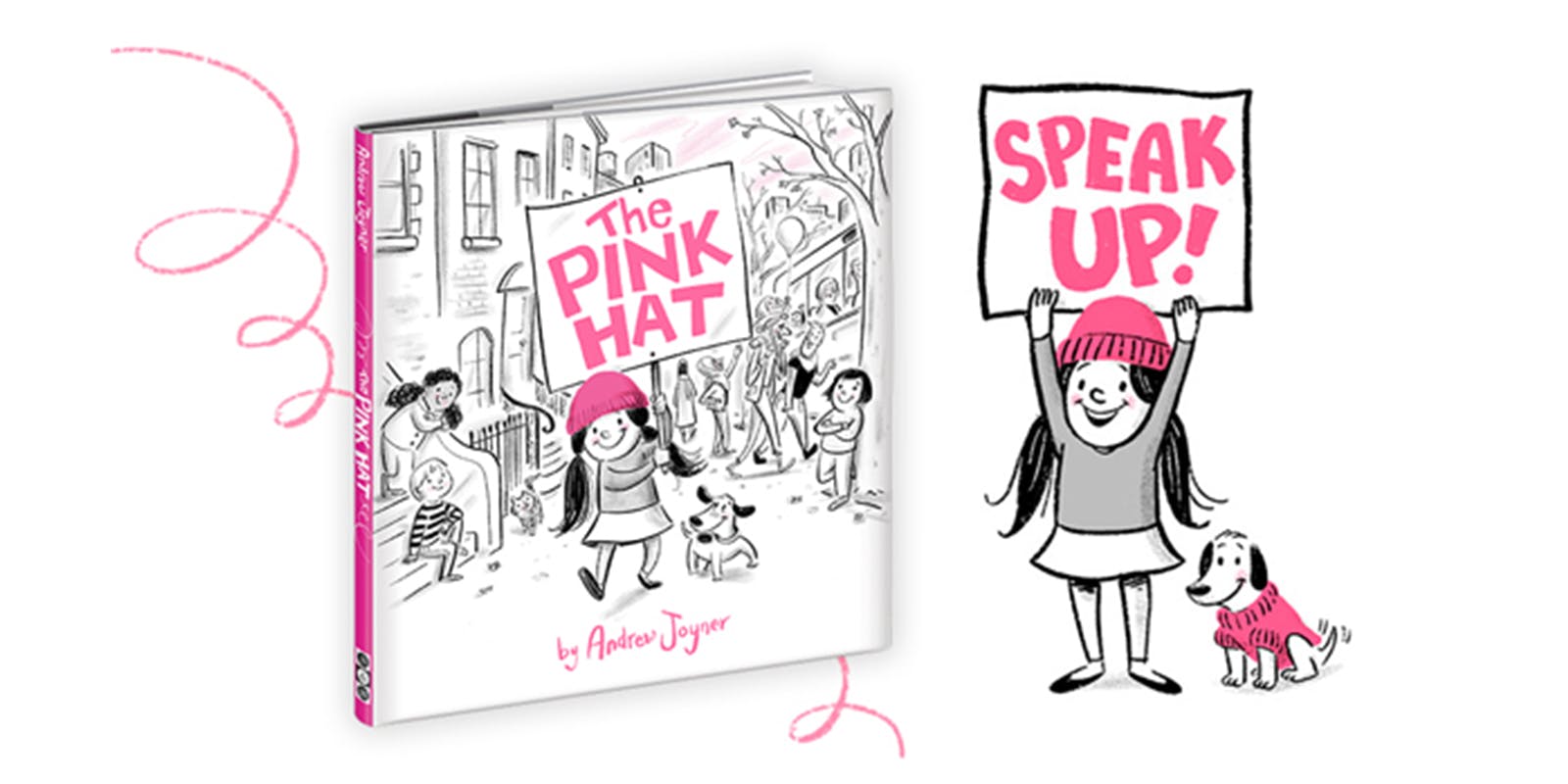

Andrew Joyner is an Australian illustrator whose work has graced multiple children’s books, including the Boris series, The Terrible Plop, Too Many Elephants in the House (both written by Ursula Dubosarsky), How Big is Too Small (with Jane Godwin) and 2017’s Blue the Builder’s Dog (with Jen Storer). His authorial picture book debut, The Pink Hat, is a timeless and timely story that celebrates girls and women and equal rights for all.

By Andrew Joyner

To me, the Woman's March on 21 January 2017 was the way forward. Suddenly, all these women and children and men had built a path to a future that seemed impossible just a day before. I loved its creativity and imagination and intelligence. It was a witty and inventive spectacle that turned something light and whimsical – a knitted, pink, cat-eared hat – into a powerful feminist symbol. Still, at the time I had no idea it would lead to a picture book.

I guess inspiration rarely takes a straight path. The initial spark for The Pink Hat was a conversation with my 14-year-old son about masculinity and role models. In fact, I first imagined the main character as a boy who finds a pink hat and joins the March. But clearly a girl belonged at the centre of the story. As soon as I drew that girl marching in her pink hat, the book started to take shape. She gave the story its power and focus.

There was a reason I dedicated The Pink Hat to ‘all the women who march us forward.’ That’s because I can’t imagine progress without feminism. At a time when the world seemed to be spinning backwards, the Women’s March gave me, and I’m sure many people around the world, hope for our future. So perhaps The Pink Hat is also my way of saying thank you.

I wanted the story to be open to any reader anywhere in the world, so I set it in a generic city, and avoided any specific reference to the US election (or Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton). But I did try to incorporate imagery into the book which would reference some of the specifics of the March. Some of it’s more obvious, such as the reference to the date of the March on the little calendar on the girl’s nightstand.

Some of the imagery is more subconscious and non-literal. For example, the bus that the girl takes home. Of course, in the story the bus is not going to the Women’s March, but buses were a significant element in the march, transporting thousands of women from around the US to Washington. So I wanted a bus to be a prominent image, especially when the narrative takes a bit of a turn and the girl becomes the main focus. When I showed the book to my sister-in-law, she even thought the African-American woman sitting at the front of the bus was an allusion to Rosa Parks. Definitely an unconscious allusion on my part, but I’ll take it!

One intentional historical symbol in the book is the statue in the park (when the girl is chasing the dog) – it’s a suffragette, although it’s not particularly obvious. There’s also the knitting of the hat by a woman who observes the March but doesn’t march herself. Many of the hats were knitted by women around the US who couldn’t actually join the march themselves.