Perilous steps to becoming the youngest Australian to climb Everest.

Known as Sagarmatha in Nepal and Chomolungma in Tibet, the mountain most Australians know as Everest is almost 8,850 metres high and the proving ground of mountaineers from around the globe. The summit is an incredibly hostile environment, with temperatures dipping below -60°C and winds topping 300 km/h. It’s an incredibly dangerous place – the last year without known fatalities on the mountain was 1977, and it’s claimed the lives of somewhere in the vicinity of 280 climbers.

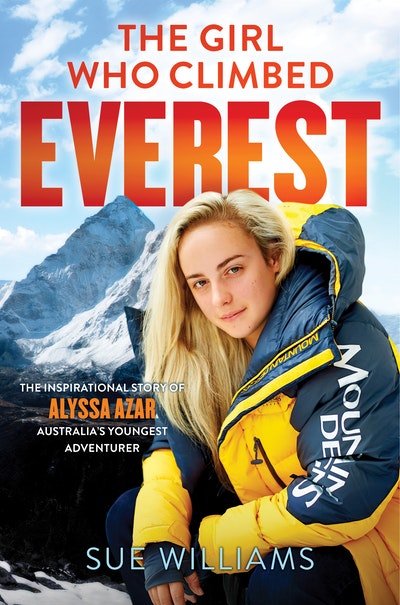

So what would inspire a teenage girl from country Queensland to attempt to ascend the world’s highest peak? In Sue Williams’ The Girl Who Climbed Everest, Alyssa Azar, the youngest Australian to do so, answers this question in spectacular style. From walking the Kokoda Track at just eight years old to reaching the top of the world at age nineteen, Alyssa’s story is one of finding the courage and motivation to keep going in the face of overwhelming danger and adversity. After being turned back from Everest’s summit on two attempts – once by an avalanche and a second time by a cataclysmic earthquake – Alyssa refused to give up. Her message: we can achieve anything if we dare to dream big. Straight from the pages of The Girl Who Climbed Everest, from the chapter titled ‘Ready to Risk Everything’, as Alyssa prepares for her final attempt at the peak we examine some of the challenges she faces on her way to the top.

[Alyssa] knows it’s going to be the hardest thing she’s ever done, and probably the most life-changing, but she feels as ready as she’ll ever be. ‘Of course I do get nervous,’ she says. ‘Part of it is the danger, and part is that I want so much to do well. I’d be lying if I didn’t admit I get scared at times. A goal like that is exhilarating, but it can also be daunting. I know it’s going to be painful. We all have our psychological demons. But pain is just a factor of the mind, and I’m learning to control my mind and body, so I’ll have more and more tolerance to pain.

‘The hardest thing for me is having some people say there’s no way I’ll be able to climb Everest. I find that very difficult but it makes me even more determined never to quit.’

As well as the journals she keeps, she takes another small hardback notebook and writes out once again all the quotations she likes to keep her motivated, as well as poems and fragments of speeches. Any time she feels self-doubt, she goes straight back to the words she’s written to keep her feeling strong. She also writes lists of things she needs to do for the future, her professional ambitions and her personal goals. She wants to learn to drive, buy her own car, get her own place, earn her own income, be independent. She wants to climb the rest of the Seven Summits and all the other 8000ers [mountains over 8000 metres]. But first, above everything else, she wants to get to the top of Everest.

She’s well aware of the dangers lying in wait with every step. The first major difficulty of the South Col route will come on the very first day after Base Camp, with the Khumbu Icefall at the head of the glacier. Here, crevasses open without warning, and seracs can thunder down.

‘That’s probably the most dangerous part of the whole climb,’ says one of Australia’s most experienced and skilled mountaineers, Andrew Lock, ‘because it’s a moving glacier and massive blocks of ice as big as home units will just collapse without warning. There’s no way of avoiding them. The first step onto the icefall could be your last.’ Camp I lies just above the icefall.

Between Camp II and III, there’s the Lhotse Face, a steep wall of ice, which can also prove perilous, he says. ‘It’s exposed pre-monsoon season and it’s very hard ice. There are lots of places where you can slip and where your crampons don’t bite. It’s scary when you slip and fall down for a few metres and are then stuck there, hanging onto the rope. Then between Camps III and IV there’s the Yellow Band, which can be a real scramble over rocks, and the Geneva Spur over loose steps is tricky, although you’re roped all the way. Then there are the challenges of the Death Zone…’

Altitude is always difficult and all climbers fear a negative reaction to it. For Alyssa though, it might be more difficult than for older people. She’s still very young to be doing all this, believes Professor Chris Gore, who’s in charge of physiology and altitude training at the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra.

‘Marathon runners are considered to be at their best in their early and late thirties because of the mental attitude to the sport, and physiologically, you don’t get close to your peak until the late teens, early twenties,’ he says. ‘Women also have lower haemoglobin concentrations than men, which is a lesser ability to transport total amounts of oxygen through the body.’

Professor Gore lost a good friend on Everest and knows exactly the kind of risks Alyssa will be facing. ‘If she succeeds, I think it would be extraordinary, a remarkable feat. The Death Zone is very dangerous. Those who’ve climbed without oxygen often sustain long-term cognitive effects as a result. Some of the ones I’ve spoken to say their memory and cognitive functioning has never been the same since. But for those who dare to dream and want to inspire us, all power to them!’

Happily, many of the experts Alyssa’s been learning from are confident she’s up to the challenge.