- Published: 19 September 2023

- ISBN: 9781761043772

- Imprint: Michael Joseph

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 432

- RRP: $32.99

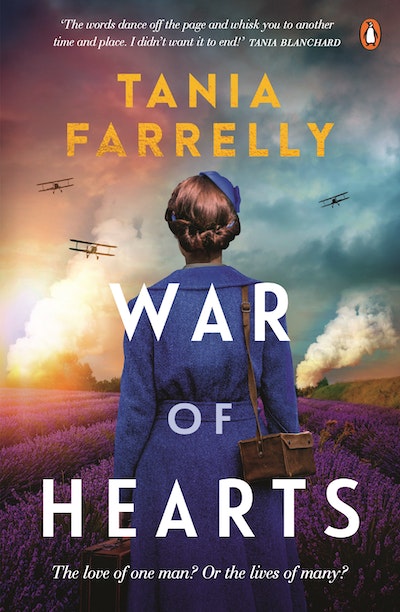

War of Hearts

Extract

Grace Winter strode through the sun-drenched throng in Times Square with the patriotic vigour of a red-blooded American. The morning streets were a glorious mess with their honking automobiles, rattling trolley cars, horse-drawn buggies and the smell of gasoline all mingling with pedestrians, heads down, papers open, devouring the news of America’s entry into the war. Grace dodged them all with a smile of self-satisfaction. They would never imagine that the woman they were passing had not only written some of that news but would also soon be making headlines herself as the New York Times’ first official female war correspondent. That’s if her instincts served her correctly and all went to plan today.

She skirted a tray-truck cart topped with Harlem’s finest belting out rag-time tunes designed to lure their brethren to enlist, walked directly beneath a ladder, then turned to look up at the illustrated Flagg posters people were gluing up: Buy Liberty Bonds they shouted from every spare square inch of Manhattan’s real estate. She sidestepped a newsie touting the morning’s papers, slowing to scan the front page held high in his hand, imagining for a gleeful, fanciful moment her name emblazoned across tomorrow’s edition, before dashing in front of a squadron of advancing black Model-Ts, unwilling and unable to wait for her news.

At the gilded entrance to the New York Times building, she tightened the bright yellow scarf around her neck, took a deep breath, tucked a loose copper curl back into her low bun, then walked in.

‘Miss Winter, gut mornin’!’ sang Mr Becker, the wizened little elevator attendant, rattling the cage door open for her to squeeze into the already packed conveyance. She caught a couple of men glancing at Mr Becker as if to say, ‘You sure this thing can hold the extra weight?’ but wiggled in with a smile of apology as Mr B took his seat on the red elevator stool and pulled the lever to shunt them upstairs. Everyone was silent as the Otis thunked through its gears. Ker thunk. Ker thunk. Ker thunk. A couple of women alighted at the typing pool on the third, and Larry from Sports straightened his tennis visor, popped in a Wrigley’s to cover his stale alcohol breath and hopped out on the fifth. Most of the other men got off at advertising on the sixth while she kept rising, proudly, to the eighth.

‘You’re looking in fine fettle this morning, Miss Winter,’ Mr Becker said when the elevator had emptied. ‘If I’m not mistaken that’s a new scarf you’re wearing today. Expecting something special?’

‘Thank you, Mr B, your eye is as quick as your mind, as always.’ She handed the old man a paper bag full of the caramels they both loved, as was her habit. She’d met Mr B years ago at a German Friendly Society ball and they’d taken a shine to one another. She’d helped him get his job here at the Times, and he liked to fill her in on the elevator gossip.

‘And an extra big bag of sweeties today?’ His brow riddled.

‘I’m expecting big things!’

‘The war correspondent job?’

She gave him a coy smile. ‘What’s the news on the eighth?’

‘Well, McElrod is grinding his teeth, his tie was completely skew-whiff this morning and he forgot to say how-di-do.’

‘Oh dash it. Doesn’t bode well.’ Her boss wasn’t the snappiest dresser but he at least always liked to keep a vertical necktie: off-centre meant agitated.

‘Redman has a pep in his step and is flirting with the girl from advertising.’

She rolled her eyes. ‘Nothing new in that.’

‘There’s a new mail boy on staff too, George, and everyone is ignoring him.’

‘I’ll be sure to give him some encouragement.’

‘And be sure to give me your news later, won’t you?’ He squinted a curious eye.

‘Quid pro quo, as always.’ Grace grinned, straightened the Peter Pan collar of her new blue serge dress then stepped out into the sea of black-suited men leaning over desks, some scribbling furiously, some hammering typewriters with their pointer fingers and all with cigarettes puffing like tiny smokestacks of intellectual industry.

The editorial floor of the Times was a hound whose neurons fired bullets of thought onto copy paper with every typewritten word, and the words this morning were focused on War! With a capital W – the call for men to register for the draft, the celebration of General Pershing’s entrance onto the European stage and the Entente’s bloody arm wrestle over Passchendaele.

Grace sat at her desk and opened the top folder, which detailed her investigations into the suspected spy network of a New York baroness, while simultaneously staring across at the man who had her fate in his hands. Any minute now her sub-editor, Mr McElrod, would look up, light a stogie, and call her in to give her the good news.

The new mail boy cut across her view, wrestling his envelope-laden trolley between the desks. ‘Miss Winter.’ He raised his peaked cap, then riffled through a letter stack and handed her a multicoloured wad.

‘Thank you, George, and may I say you’re doing an extra fine job for a newcomer.’ Grace gave him a warm smile. The men would never bother with such pleasantries.

‘Thank you, ma’am.’ He stood bug-eyed, surveying the top folder open on her desk, and Grace put his interest down to the fact she was a minor celebrity round these parts, being the only female reporter on the editorial floor.

‘Thank you, George, you can go now.’

He blushed, turned and beetled off with his trolley.

With one eye on her mail and one still on her boss, she began prioritising the letters in order of importance. There were the usual communiqués from the top; the censor’s new wartime Dos and Don’ts; and a thick blue envelope that caught her eye – her heart gave an Otis-style ker thunk. This envelope was not the sort her regular informant preferred, nor was the font typical (her informant’s typewriter had a droopy-looking r), but still, she could just about smell the good oil leaking out of this one. She raked her letter opener through the seal impatiently and pulled out a grainy photograph along with a note: Re: Charlie Ryan’s Music Box. Herewith proof of existence. Post reward check by return mail.

Grace’s heart accelerated. She leaned across her typewriter, grabbed her magnifying glass from an old jam tin, and ran it over the photograph to compare it with her reference illustration. A familiar disappointment washed over her and she tossed the photograph on the scrap-heap with the other fakes.

Strange, after her years of reporting every kind of human tragedy and joy, that Charlie Ryan’s kidnapping case still had her spellbound. When she was a schoolgirl the boy’s innocent blue-eyed face had been featured on every tin of delicious Little Boy Blue Caramels all across America, and he’d signified all that was good and sweet and true about her adopted homeland. When he had disappeared in 1904, Grace had grieved terribly, even badgered Tante Marthe to take her to his public memorial service in upstate New York. Eleven years later, she had used her position as a reporter at the Times to rekindle public interest by personally stumping up half the reward for the return of Charlie’s missing music box. For two years she’d interviewed witnesses, developed a shortlist of suspects and amassed hundreds of photographs of fake music boxes, all missing the distinctive birds-in-flight symbol she’d deliberately left off her description of the silver trinket.

She had, however, uncovered that the original investigation had been a sham: the police had been paid off and the rest was a murky tale of gangs, threats and murders over gambling debts. Did the gangsters get Charlie, or was it the nanny – or Albert Fish, the notorious paedophile referred to as the Gray Man of New York? The coroner had declared death by foul play due to the discovery of a body that might have been Charlie’s, and the case went cold.

‘Wint-ahh!’ McElrod bellowed from the smoky depths of his windowed office.

Grace stood and smoothed down her skirt. ‘Finally!’ she whispered, tightening her yellow scarf again then weaving her way between the desks into McElrod’s office, contemplating how she should react to the news of her promotion. Would it be too familiar to give him a hug? Should she just hold out her hand for a hearty, professional shake, or perhaps accept a cigar to light for ceremonial purposes as the men liked to do?

Yes. She liked that one. Then the whole office would know. But as she stood by McElrod’s desk awaiting permission to sit in the visitor’s chair, he left her standing, his gaze fixed on the smouldering mound of spent cigars in his ashtray.

‘Winter. There’s going to be some changes around here.’

‘That’s what I’m counting on, sir,’ she said less confidently than she intended to. The tenor of his voice didn’t sound right. Her boss was famously gruff, even in the throes of a compliment, but today there was an unusual vexation in his tone, plus he hadn’t invited her to sit down. Her eyes landed on the special report she’d submitted yesterday about New York’s pacifist movement. It had been stamped Trash in red ink.

‘Fact is – this meeting isn’t what you think it is.’

Her stomach fluttered with the mixture of fear and self-doubt that always came with any hint of his disapproval. ‘So, you need changes to the Pacifist story?’

‘Nope. This story, as they say in the classics, is as dead as the dodo.’

‘Why?’

‘You’re going to find this a bitter pill to swallow,’ he said, his eyes glued to hers.

‘What, sir?’

‘Truth is the first casualty of war, Winter. The censors are God. Get used to it.’

McElrod settled back, filling his broad brown leather chair. He was a fair man, usually, when it came to rewarding good journalism. He’d promoted her above other capable men and he was, after all, her beloved mentor. But in this moment, all that seemed very past tense.

‘And ah’ – his top lip twitched – ‘Redman is set to get the correspondent’s job. He’ll be in Europe by Christmas and, ah, you’re being seconded to the social pages, effective immediately.’

She groped at the edge of his desk to steady herself. ‘What? No! Why?’

McElrod averted his eyes and lowered his voice in an uncharacteristically apologetic way. ‘Orders. All the gals in the socials are hotfooting it to the altar before their beaus depart for war – so as a single woman, I’m afraid you’re it.’

‘I can’t.’ She breathed. ‘Can’t you send a cub out for the social pages?’

‘No. The cubs are all men, it doesn’t work that way.’

‘I thought you said I’d be chosen for Europe.’ She worked to catch his gaze.

‘Dammit, Winter.’ He jerked a thumb towards the visitor’s chair. ‘Sit – and listen.’

Grace drew in a deep breath and sat down, trying to hold her panic at bay as McElrod rubbed a hand across his jaw, assessing her in the way one might assess a vital chess move.

‘You’re German, aren’t you, Winter?’

She sat back, stunned. ‘What?’

‘A Kraut. Hun. Boche.’

‘I’m American.’

‘But your last name is really Wettin, and that name is German.’

‘It was my name. If it’s good enough for King George to change his family name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor, then surely I can anglicise mine to Winter?’

‘The whole truth, Winter.’

Grace’s composure crumpled. ‘I was born in Germany, yes. But my mother was English. My father was Prussian by birth, but I grew up in France and lived half of my life right here in Manhattan and I’m just like everybody else in Gotham – a New York City polyglot.’

‘Hmmm.’ He eyed her as though they hadn’t been mentor and apprentice these last four years, as though he hadn’t read her stories with a brow raised in admiration and said, ‘You have a precocious talent for observation, Winter.’ Instead he said, ‘But you live in Yorkville in the heart of the German quarter with your German aunt and you speak – yes, that’s right – German.’

‘My aunt died many years ago.’ Her voice thickened with the swell of emotion. ‘Yes, I speak German, but that’s hardly a crime.’

‘Might be now,’ he muttered.

‘I also speak French and a smattering of Dutch and Spanish. What is this, sir? An interrogation?’

‘You should be aware of the remit of the new American Protective League, the APL, which is oriented towards curbing the German problem on our shores.’

‘What’s that got to do with me?’

‘German blood and a press badge?’ He eyed her. ‘Think about it.’

‘But the APL are just a bunch of entitled bankers turned vigilantes.’

‘And they’ve got the goddamn president’s imprimatur to root out anyone they see as suspect. Your parvenus and long-haired pacifists in Greenwich Village and anyone within their radius will be top of the list.’ He glanced away. ‘Fact is, you are what the authorities are calling a hyphenated American, so you need to keep your head down.’

‘I don’t understand.’

He paused, then crooked his index finger. She approached his desk and leaned forwards.

‘Winter. There are eyes and ears everywhere here,’ he whispered. ‘So keep your head down and do what you’re told.’ He gave her his ol’ incisive look, then picked up a folder and slapped it on his desk, ‘Right then.’ He cleared his throat. ‘I need a juicy piece for page fourteen, like the one on the missing Follies girl.’ He tapped the face of his watch. ‘You’ve got around an hour till deadline.’

‘But . . .’

‘Fine. If you don’t want it, I’ll get Redman to do the piece.’

She looked through the glass into the press room. There was Redman, chatting up another girl from the typing pool. He wasn’t the sharpest investigative mind. Hardly in her league. The correspondent’s job wasn’t his just yet – she still had eight weeks to claw it back.

‘Leave it with me, sir.’

Back in her chair Grace took a deep breath to steady her racing heart. Someone (McElrod?) had been digging around in her past. Were all the other men suspicious of her German heritage too?

She gazed around the room. No. They were all frantic, self-absorbed journeymen, trying their damnedest to beat her to the Western Front. Her gaze came to rest on Fysh Redman – ‘Red’, as he liked to call himself. He ran his palm sideways across his jet-black fringe in the way he always did when he was concentrating. If anyone was going to be an APL vigilante it was handsome, cock-sure Redman. Smart, lazy, with high-profile contacts and a tendency to speak about himself in the third person. The man was a shark.

She popped a caramel into her cheek and began doodling: Redman with his big Sozodont smile as a great white shark, McElrod as a militant helmet-wearing toad she named General Obedience, a fat cigar drooping out of his thick lips. She tapped the end of her nose with her pencil, then drew a circling bait ball of fish around them to represent the general public and labelled them Censored Schools of Thought. And then behind a curtain of coral she drew herself as a minnow, watching on with a magnifying glass in one fin and a pen in the other, ready to document the truth.

The Secret Truth of Our (Highly Censored) Times by The Manhattan Minnow, she headlined it. There. That felt better. Drawing caricatures like this was a silly cathartic thing she’d never quite grown out of.

She glanced up to find Redman staring at her and shoved the drawing into her handbag.

‘What are you staring at?’

‘Heard the news?’

She held Redman’s eye. ‘That’s generally what I write, Redman – you ought to try it someday.’

‘Good one, Winter.’ He slapped a knee in fake amusement and swept her insult away. ‘Just thought you’d wanna know that your pal Mr Becker has been fired.’ He leaned back in his chair and twirled his pencil nonchalantly between his fingers.

‘What?’ She glanced towards the elevators. ‘Not Mr B? Why?’

He gave a wry smile. ‘Washington has warned everyone to be on alert for pro-Germans in their midst. Bunch of elevator boys in New York hotels have been accused of spying, so the Times is taking no chances.’

Grace tried not to let the extent of her disappointment show as she turned away from Redman’s laugh and tipped her hourglass upside down. Attempting to refocus to her work so as not to betray her emotions, she reached under her desk into her little pharmacist’s cabinet, knowing the scraps of evidence, clippings and photographs housed there were her lifeline to a fast story. With her mind on Mr B – where would he go? What would happen if he couldn’t find a job elsewhere? – she ran her fingers along the tops of the filing card tabs till she arrived at Z for Ziegfeld, but then remembered she didn’t need it. The girl wasn’t missing at all – her informant had said the girl faked her own disappearance and ran away from an abusive father into the arms of her young lover. She wanted very much to stay lost.

Grace stared at her blank copy paper, forcing her attention back to the task at hand and its impending deadline. She’d always taken pride in telling the truth in black and white, but this girl’s life was at stake. How to weave the words? Ah! She stabbed her pencil in the air, finding a headline that would earn McElrod’s approval by saving him a job.

Who is Ziegfeld’s most mysterious Folly? Subhead: Hell’s Kitchen serves up more underworld intrigue. She punched out a piece that threw up an array of plausible (but carefully obtuse) theories on the life of the Follies girl, pulled her copy paper up through the roller, then marched directly into McElrod’s office and handed him her article.

‘Mr McElrod, about Mr Becker.’

McElrod raised a dismissive hand as he read the piece.

‘Good headline,’ he said dispassionately. ‘Not your best work – but it’ll do. Now get acquainted with the socials: start with this Helena Rubinstein woman. She’s expanding her cosmetics range across America, and taking it up to her rival Elizabeth Arden.’

‘What? No!’ Her head whirled. ‘My background is in medicine, not puffery and make-believe.’

‘Winter. That statement alone proves your naivety. You are too green for the realities of war reporting.’

‘Please, sir, give me a chance. What about my developing story on the spy baroness?’

‘Nope.’ He sucked on his stogie and swung his chair to look out to the water-towered rooftops of Manhattan as the sun moved behind a cloud and turned the atmosphere hauntingly grey.

‘Sir, please. Give me a chance to prove myself. You know I’m better than Redman.’

He took up his red grease pencil and began editing another piece of copy. ‘One day,’ he said without looking up, ‘you’ll thank me for all this.’

‘For punishing me?’

‘No, for protecting you. Have a good evening, Winter.’

War of Hearts Tania Farrelly

A heart-stopping novel of love in a time of war, ideal for fans of Fiona McIntosh and Natasha Lester.

Buy now