- Published: 1 December 2020

- ISBN: 9780241374511

- Imprint: Penguin General UK

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $24.99

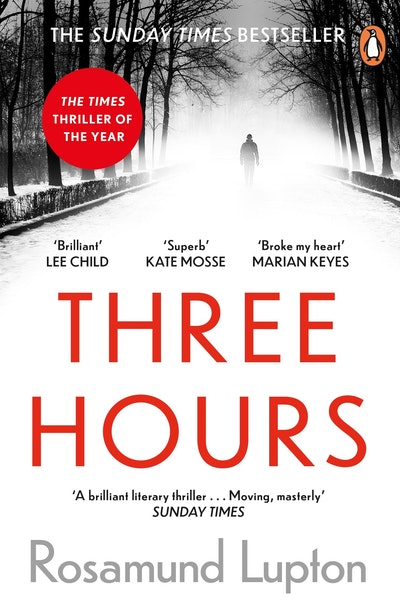

Three Hours

The Top Ten Sunday Times Bestseller

Extract

PART ONE

And you? When will you begin that long journey into yourself?

Rumi (1207– 1273)

1.

9.16 a.m.

A moment of stillness; as if time itself is waiting, can no longer be measured. Then the subtle press of a fingertip, whorled skin against cool metal, starts it beating again and the bullet moves faster than sound.

It smashes the glass case on the wall by the headmaster’s head, which displays medals for gallantry awarded in the last World War to boys barely out of the sixth form. Their medals turn into shrapnel; hitting the headmaster’s soft brown hair, breaking the arm of his glasses, piercing through the bone that protects the part of him that thinks, loves, dreams and fears; as if pieces of metal are travelling through the who of him and the why of him. But he is still able to think because it’s he who has thought of those boys, shrapnel made of gallantry, tearing apart any sense he’d once had of a benevolent order of things.

He’s falling backwards. Another shot; the corridor a reverberating sound tunnel. Hands are grabbing him and dragging him into the library.

Hannah and David are moving him away from the closed library door and putting him into the recovery position. His sixth-formers have all learnt first aid, compulsory in Year 12, but how did they learn to be courageous? Perhaps it was there all this time and he didn’t notice it; medals again, walked past a hundred times, a thousand.

He tries to reassure them that even if it looks bad – he is pretty sure it must look very bad indeed – inside he’s okay, the who of him is still intact but he can’t speak. Instead sounds are coming out of his mouth that are gasps and grunts and will make them more afraid so he stops trying to speak.

His pupils’ faces look ghostly in the dim light, eyes gleaming, dark clothes invisible. They turned off all the electric lights when the code red was called. The Victorian wooden shutters have been pulled shut over the windows; traces of weak winter daylight seep inside through the cracks.

He, Matthew Marr, headmaster and only adult here, must protect them; must rescue his pupils in Junior School, the pottery room, the theatre and the English classroom along the corridor; must tell the teachers not to take any risks and keep the children safe. But his mind is slipping backwards into memory. Perhaps this is what the shrapnel has done, broken pieces of bone upwards so they form a jagged wall and he is stuck on the side of the past. But words in his own thoughts grab at him – risks, safe, rescue.

What in God’s name is happening?

As he struggles to understand, his thoughts careen backwards, too fast, perilously close to tipping over the edge of his mind and the blackness there; stopping with the memory of a china-blue sky, the front of Old School bright with flowering clematis, the call of a pied flycatcher. His damaged brain tells him the answer lies here, in this day, but the thoughts that have brought him to this point have dissolved.

Hannah covers Mr Marr’s top half with her puffa jacket and David covers his legs with his coat, then Hannah takes off her hoody. She will not scream. She will not cry. She will wrap her hoody around Mr Marr’s head, tying the arms tightly together, and then she must try to staunch the bleeding from the wound in his foot, and when she has done these things she will check his airway again.

No more shots. Not yet. Fear thinning her skin, exposing her smallness. As she takes off her T-shirt to make a bandage she glances at the wall of the library that faces the garden, the shuttered windows too small and too high up for escape. The other wall, with floor-to-ceiling bookcases, runs alongside the corridor. The gunman’s footsteps sound along the bookcases as he walks along the corridor. For a little while they thought he’d gone, that he’d walked all the way to the end of the corridor and the front door and left. But he hadn’t. He came back again towards them.

He must be wearing boots with metal in the heel. Click-click click-click on the worn oak floorboards, then a pause. No other sounds in the corridor; nobody else’s footsteps, no voices, no bump of a book bag against a shoulder. Everyone sheltering, keeping soundless and still. The footsteps get quieter. Hannah thinks he’s opposite Mrs Kale’s English classroom. She waits for the shots. Just his footsteps.

Next to her, David is dialling 999, his fingers shaking, his whole body shaking, and even though it’s only three numbers it’s taking him ages. She’s worried that the emergency services will be engaged because everyone’s been phoning 999, for police though, not for an ambulance, not till now, and maybe they’ll be jamming the line.

When I am Queen . . . Dad says to her, and she says, When I am Queen there’ll be a separate line for the police and ambulances and fire service, but she can’t hear Dad’s voice any more, just David’s saying, ‘Ambulance, please,’ like he’s ordering a pizza at gunpoint, and now he’s waiting to be put through to the ambulance people.

It was the kids who started the rush on 999 calls, not only directly but all those calls to mothers at work, at home, at coffee mornings, Pilates, the supermarket, and dads at work, mainly, but some at home like hers, and the parents said: Have you phoned the police? Where are you? Has someone phoned the police? I’m coming. Where exactly are you? I’m on my way. I’m phoning the police. I’ll be right there. I love you.

Or variations on that call, apart from the I love you; she’s sure all the parents said that because she heard all the I love you too-s. Dad said all that. She’d been in the English classroom then, where phones are allowed. Not allowed in the library, left in a basket outside, switched o . David is using hers.

She’s trying to rip her Gap T-shirt to make a tourniquet for Mr Marr’s foot, but the cotton is too tough and won’t tear and she doesn’t have scissors. She only wears this T-shirt in winter under something else because everyone wears Superdry or Hollister, not Gap, not since lower school, and now she’s in front of loads of people, including the headmaster, wearing only her bra, because her clothes have had to turn into blankets and bandages, and she doesn’t feel any embarrassment, just ridiculous that she ever minded about something as stupid as what letters were on a T-shirt. She wraps the whole T-shirt around his foot.

Click-click click-click in the corridor. The door doesn’t have a lock. She goes to join Ed, who’s pulling books out of the bookcase nearest to the door, FICTION W–Z, and piling them up against it.

Why’s he just walking up and down the corridor?

She tries not to listen to the footsteps but instead reads the titles of the books as they use them to barricade the door: The Color Purple by Alice Walker, Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh – click-click – The Time Machine by H. G. Wells – click-click – To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, Godless in Eden by Fay Weldon, The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. She imagines bullets going through the books, leaving splashes of purple, a wrecked time machine, a smashed lighthouse lamp, and everything going dark.

She returns to Mr Marr while Ed continues adding more books to the large heap against the door. As she kneels next to him, Mr Marr’s eyes flicker and catch hers. Before he was shot Mr Marr told her love is the most powerful thing there is, the only thing that really matters, and as she remembers this she digs the palm of her hand into her T-shirt bandage covering his foot to staunch the bleeding.

But the word shot lodges in her mind, cruel and bloody, making her nauseous. Shot isn’t written down or spoken so she can’t cover it up with her hand or shout it down and she wonders what a mind-word is if it can’t be seen or heard. She thinks that consciousness is made up of silent, invisible words forming unseen sentences and paragraphs; an unwritten, unspoken book that makes us who we are. Mr Marr’s eyes are closing. ‘You have to stay awake, Mr Marr, please, you have to keep awake.’ She’s afraid that if he loses consciousness the silent invisible book of him will end.

The footsteps sound louder again alongside the library wall, coming back towards them. She has to try to be calm, has to get a grip. Dad says she’s resourceful and brave; George in Famous Five, Jo in Little Women. Never a pretty girl, especially not a pretty teenage girl, she has developed a sturdy character. Rafi says she’s ya amar, like the moon, but she doesn’t believe him.

Ed has moved on to FICTION S–V, trying to stay out of the line of fire if he shoots, throwing books on to the pile from the side. There’s many more books at the bottom, new ones sliding down from the summit to the base.

The footsteps get to outside their door and stop. She holds her breath, hears her heart beating into the silence, then the footsteps walk past.

Three Hours Rosamund Lupton

The extraordinary top ten Sunday Times bestseller about a school under siege

Buy now