- Published: 4 February 2020

- ISBN: 9781405935999

- Imprint: Michael Joseph

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 400

- RRP: $24.99

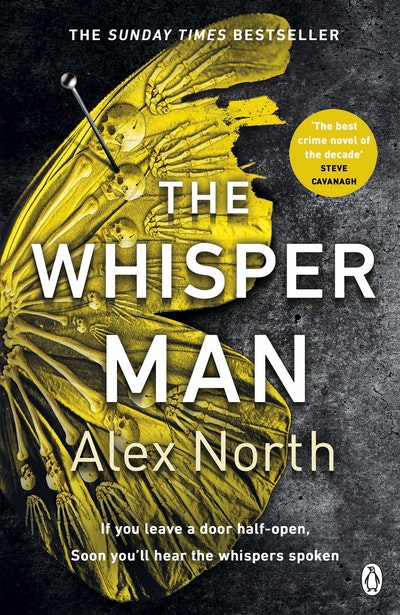

The Whisper Man

Extract

Because you know what? I was absolutely fucking terrified. I grew up as an only child, completely unused to babies, and yet there I was – responsible for one of my own. You were so impossibly small and vulnerable, and me so unprepared, that it seemed ludicrous they’d allowed you out of the hospital with me. From the very beginning, we didn’t fit, you and I. Rebecca held you easily and naturally, as though she’d been born to you rather than the other way around, whereas I always felt awkward, scared of this fragile weight in my arms and unable to tell what you wanted when you cried. I didn’t understand you at all.

That never changed.

When you were a little older, Rebecca told me it was because you and I were so alike, but I don’t know if that’s true. I hope it isn’t. I’d always have wanted better for you than that.

But regardless, we can’t talk to each other, which means I’ll have to try to write all this down instead. The truth about everything that happened in Featherbank.

Mister Night. The boy in the floor. The butterflies. The little girl with the strange dress.

And the Whisper Man of course.

It’s not going to be easy, and I need to start with an apology. Over the years, I told you so many times that there was nothing to be afraid of. That there was no such thing as monsters.

I’m sorry that I lied.

PART ONE

July

One

The abduction of a child by a stranger is every parent’s worst nightmare. But statistically, it is a highly unusual event. Children are actually most at risk of harm and abuse from a family member behind closed doors, and while the outside world might seem threatening, the truth is that most strangers are decent people, whereas the home is often the most dangerous place of all.

The man stalking six-year-old Neil Spencer across the waste ground understood that only too well.

Moving quietly, parallel to Neil behind a line of bushes, he kept a constant watch on the boy. Neil was walking slowly, unaware of the danger he was in. Occasionally, he kicked at the dusty ground, throwing up chalky white mist around his trainers. The man, treading far more carefully, could hear the scuff each time. And he made no sound at all.

It was a warm evening. The sun had been beating down hard and unrestrained for most of the day, but it was six o’clock now and the sky was hazier. The temperature had dropped and the air had a golden hue to it. It was the sort of evening where you might sit out on the patio, perhaps sipping cold white wine and watching the sun set, without thinking about fetching a coat until it was dark and too late to bother.

Even the waste ground was beautiful, bathed in the amber light. It was a patch of shrub land, edging the village of Featherbank on one side, with an old disused quarry on the other. The undulating ground was mostly parched and dead, although bushes grew in tough thickets here and there, lending the area a maze-like quality. The village children played here sometimes, although it was not particularly safe. Over the years, many of them had been tempted to clamber down into the quarry, where the steep sides were prone to crumble away. The council put up fences and signs, but the local consensus was that they should do more. Children found ways over fences, after all.

They had a habit of ignoring warning signs.

The man knew a lot about Neil Spencer. He had studied the boy and his family carefully, like a project. The boy performed poorly at school, both academically and socially, and was well behind his peers in reading, writing and maths. His clothes were mostly hand-me-downs. In his manner, he seemed a little too grown-up for his age – already displaying anger and resentment towards the world. In a few years, he would be perceived as a bully and a troublemaker, but for now he was still young enough for people to forgive his more disruptive behaviour. ‘He doesn’t mean it,’ they would say. ‘It’s not his fault.’ It had not yet reached the point where Neil was considered solely responsible for his actions, and so people were forced instead to look elsewhere.

The man had looked. It wasn’t hard to see.

Neil had spent today at his father’s house. His mother and father were separated, which the man considered a good thing. Both parents were alcoholics, functioning to wavering degrees. Both found life considerably easier when their son was at the other’s house, and both struggled to entertain him when he was with them. In general, Neil was left to occupy and fend for himself, which obviously went some way to explaining the hardness the man had seen developing in the boy. Neil was an afterthought in his parents’ lives. Certainly, he was not loved.

Not for the first time, Neil’s father had been too drunk that evening to drive him back to his mother’s house, and apparently also too lazy to walk with him. The boy was nearly seven, his father probably reasoned, and had been fine alone all day. And so Neil was walking home by himself.

He had no idea yet that he would be going to a very different home. The man thought about the room he had prepared and tried to suppress the excitement he felt.

Halfway across the waste ground, Neil stopped.

The man stopped close by, then peered through the brambles to see what had caught the boy’s attention.

An old television had been dumped against one of the bushes, its grey screen bulging but intact. The man watched as Neil gave it an exploratory nudge with his foot, but it was too heavy to move. The thing must have looked like something out of another age to the boy, with grilles and buttons down the side of the screen and a back the size of a drum. There were some rocks on the other side of the path. The man watched, fascinated, as Neil walked over, selected one, and then threw it at the glass with all his strength.

Pock.

A loud noise in this otherwise silent place. The glass didn’t shatter, but the stone went through, leaving a hole starred at the edges like a gunshot. Neil picked up a second rock and repeated the action, missing this time, then tried again. Another hole appeared in the screen.

He appeared to like this game. And the man could understand why. This casual destruction was much like the increasing aggression the boy showed in school. It was an attempt to make an impact on a world that seemed so oblivious to his existence. It stemmed from a desire to be seen. To be noticed. To be loved.

That was all any child wanted, deep down.

The man’s heart, beating more quickly now, ached at the thought of that. He stepped silently out from the bushes behind the boy, and then whispered his name.

Two

Neil. Neil. Neil.

DI Pete Willis moved carefully over the waste ground, listening as the officers around him called the missing boy’s name at prearranged intervals. In between, there was absolute silence. Pete looked up, imagining the words fluttering into the blackness up there, disappearing into the night sky as completely as Neil Spencer had vanished from the Earth below it.

He swept the beam of his torch over the dusty ground in a conical pattern, checking his footing as well as looking for any sign of the boy. Blue tracksuit bottoms and underpants, Minecraft T-shirt, black trainers, army-style bag, water bottle. The alert had come through just as he’d been sitting down to eat the dinner he’d laboured over, and the thought of the plate there on his table right now, untouched and growing cold, made his stomach grumble.

But a little boy was missing and needed to be found.

The other officers were invisible in the dark, but he could see their torches as they fanned out across the area. Pete checked his watch: 8.53 p.m. The day was almost done, and although it had been hot this afternoon, the temperature had dropped over the last couple of hours, and the cold air was making him shiver. In his rush to leave, he’d forgotten his coat, and the shirt he was wearing offered scant protection against the elements. Old bones too – he was fifty-six, after all – but no night for young ones to be out either. Especially lost and alone. Hurt, most likely.

Neil. Neil. Neil.

He added his own voice: ‘Neil!’

Nothing.

The first forty-eight hours following a disappearance are the most crucial. The boy had been reported missing at 7.39 p.m. that evening, roughly an hour and a half after he had left his father’s house. He should have been home by 6.20 p.m., but there had been little coordination between the parents as to the exact time of his return, so it wasn’t until Neil’s mother had finally phoned her ex-husband that their son’s absence was discovered. By the time the police arrived on the scene at 7.51 p.m., the shadows were lengthening and approaching two of those forty-eight hours had already been lost. Now it was closer to three.

In the vast majority of cases, Pete knew, a missing child is found quickly and safely and returned to their family. Cases were divided into five distinct categories: throwaway; runaway; accident or misadventure; family abduction; non-family abduction. The law of probability was telling Pete right now that the disappearance of Neil Spencer would turn out to be an accident of some kind, and that the boy was going to be found soon. And yet, the further he walked, the more his gut instinct was telling him differently. There was an uncomfortable feeling curling around his heart. But then, a child going missing always made him feel like this. It didn’t mean anything. It was just the bad memories of twenty years ago surfacing, bringing bad feelings along with them.

The beam of his torch passed over something grey.

Pete stopped immediately, then played it back to where it had been. There was an old television set lodged at the base of one of the bushes, its screen broken in several places, as though someone had used it for target practice. He stared at it for a moment.

‘Anything?’

An anonymous voice calling from one side.

‘No,’ he shouted back.

He reached the far side of the waste ground at the same time as the other officers, the search having turned up nothing. After the relative darkness behind him, Pete found the bleached brightness of the street lights here oddly queasy. There was a quiet hum of life in the air that had been absent in the silence of the waste ground.

A few moments later, stuck for anything better to do right now, he turned around and walked back the way he’d come.

He wasn’t really sure where he was going, but he found himself heading off to the side, in the direction of the old quarry that ran along one edge. It was dangerous ground in the dark, so he headed towards the cluster of torchlights where the quarry search team were about to start work. While other officers were working their way along the edge, shining their beams down the steep sides and calling Neil’s name, the ones here were consulting maps and preparing to descend the rough path that led into the area below. A couple of them looked up as he reached them.

‘Sir?’ One of them recognized him. ‘I didn’t know you were on duty tonight.’

‘I’m not.’ Pete bent the wire of the fence up, and ducked under to join them, even more careful of his footing now. ‘I live locally.’

‘Yes, sir.’ The officer sounded dubious.

It was unusual for a DI to turn up for what was ostensibly grunt work like this. DI Amanda Beck was coordinating the burgeoning investigation from back at the department, and the search team here was comprised mainly of rank and file. Pete figured he had more years on the clock than any of them, but tonight he was just part of the crowd. A child was missing, which meant that a child needed to be found. The officer was maybe too young to remember what had happened with Frank Carter two decades earlier, and to understand why it was no surprise to find Pete Willis out in circumstances like this.

‘Watch yourself, sir. The ground’s a bit shaky here.’

‘I’m fine.’

Young enough to discount him as some old man as well, apparently. Presumably he’d never seen Pete in the department’s gym, which he visited every morning before heading up to work. Despite the disparity in their ages, Pete would have bet he could outlift the younger man on every machine. He was watching the ground all right. Watching everything – including himself – was second nature to him.

‘Okay, sir, well, we’re about to head down. Just coordinating.’

‘I’m not in charge here.’ Pete pointed his torch down the path, scanning the rough terrain. The beam of light only penetrated a short distance. The bed of the quarry below was nothing but an enormous black hole. ‘You report to DI Beck, not to me.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Pete continued staring down, thinking about Neil Spencer. The most likely routes the boy would have taken had been identified. The streets had been searched. Most of his friends had already been contacted, all to no avail. And the waste ground was clear. If the boy’s disappearance really was the result of an accident or misadventure then the quarry was the only remaining place that made sense for him to be found.

And yet the black world below felt entirely empty.

He couldn’t know for sure – not through reason. But his instinct was telling him that Neil Spencer wasn’t going to be found here.

That maybe he wasn’t going to be found at all.

Three

‘Do you remember what I told you?’ the little girl said.

He did, but right now Jake was doing his best to ignore her. All the other children in the 567 Club were outside, playing in the sun. He could hear the shouting and the sound of the football skittering over the tarmac, and every now and then it would thud against the side of the building. Whereas he was sitting inside, working on his drawing. He would much rather have been left alone to finish it. It wasn’t that he didn’t like playing with the little girl. Of course he did. Most of the time, she was the only one who wanted to play with him, and normally he was more than happy to see her. But she wasn’t acting particularly playful this afternoon. In fact, she was being all serious, and he didn’t like that one bit.

‘Do you remember?’

‘I guess.’

‘Say it then.’

He sighed, put the pencil down, and looked at her. As always, she was wearing a blue-and-white checked dress, and he could see the hash of a graze on her right knee that never seemed to heal. While the other girls here had neat hair, cut level at the shoulders or tied back in a tight ponytail, the little girl’s was spread out messily to one side and looked like she hadn’t brushed it in a long time.

From the expression on her face now, it was obvious she wasn’t going to give up, so he repeated what she’d told him.

‘If you leave a door half open . . .’

It should have been surprising that he did remember it all, really, because he hadn’t made any special effort to make the words stick. But for some reason, they had. It was something about the rhythm. Sometimes he’d hear a song on CBBC and it would end up going round and round in his brain for hours. Daddy had called it an earworm, which had made Jake imagine the sounds burrowing into the side of his head and squirming around in his mind.

When he was finished, the little girl nodded to herself, satisfied. Jake picked up his pencil again.

‘What does it mean anyway?’ he said. ‘It’s a warning.’ She wrinkled her nose. ‘Well – kind of anyway. Children used to say it when I was little.’

‘Yes, but what does it mean?’

‘It’s just good advice,’ she said. ‘There are a lot of bad people in the world, after all. A lot of bad things. So it’s good to remember.’

Jake frowned, and then started drawing again. Bad people. There was a slightly older boy called Carl here at the 567 Club who Jake thought was bad. Last week, Carl had cornered him while he was building a Lego fortress, and then stood too close, looming over him like a big shadow.

‘Why’s it always your dad who picks you up?’ Carl had demanded, even though he already knew the answer. ‘Is it because your mum’s dead?’

Jake hadn’t answered.

‘What did she look like when you found her?’ Again, he hadn’t answered. Apart from in nightmares, he didn’t think about what it had been like to find Mummy that day. It made his breath go funny and not work properly. But one thing he couldn’t escape from was the knowledge that she wasn’t here any more.

It reminded him of a time long gone when he had peered round the kitchen door and seen her chopping a big red pepper in half and pulling out the middle.

‘Hey, gorgeous boy.’

That was what she’d said when she’d seen him. She always called him that. The feeling inside when he remembered she was dead had the kind of sound the pepper made, like something ripping with a pock and leaving a hollow.

‘I really like seeing you cry like a baby,’ Carl had declared, and then walked away like Jake didn’t even exist.

It wasn’t nice to imagine the world was full of people like that, and Jake didn’t want to believe it. He drew circles on the sheet of paper now. Force fields around the little stick figures battling there.

‘Are you all right, Jake?’

He looked up. It was Sharon, one of the grown-ups who worked at the 567 Club. She had been washing up at the far side of the room, but had come over now, and was leaning down with her hands between her knees.

‘Yes,’ he said.

‘That’s a nice picture.’

‘It’s not finished yet.’

‘What is it going to be?’

He thought about how to explain the battle he was drawing – all the different sides fighting it out, with the lines between them and the scribbles over the ones who had lost – but it was too difficult.

‘Just a battle.’

‘Are you sure you don’t want to go outside and play with the other children? It’s such a lovely day.’

‘No, thank you.’

‘We’ve got some spare suncream.’ She looked around. ‘There’s probably a hat somewhere too.’

‘I need to finish my drawing.’

Sharon stood back up again, sighing quietly to herself, but with a kind expression on her face. She was worried about him, and while she didn’t need to be, he supposed that was still kind of nice. Jake could always tell when people were concerned about him. Daddy often was, except for those times when he lost his patience. Sometimes he shouted, and said things like, ‘It’s just because I want you to talk to me, I want to know what you’re thinking and feeling,’ and it was scary when that happened, because Jake felt like he was disappointing Daddy and making him sad. But he didn’t know how to be different from how he was.

Round and round – another force field, the lines overlapping. Or maybe it was a portal instead? So that the little figure inside could disappear from the battle and go away, somewhere better. Jake turned the pencil around and began carefully erasing the person from the page.

There.

You’re safe now, wherever you are.

One time, after Daddy lost his temper, Jake found a note on his bed. There was what he had to admit was a very good picture of the two of them smiling, and underneath that Daddy had written:

I’m sorry. I want you to remember that even when we argue we still love each other very much. Xxx.

Jake had put the note into his Packet of Special Things, along with all the other important things he needed to keep. He checked now. The Packet was on the table in front of him, right beside the drawing.

‘You’re going to be moving to the new house soon,’ the little girl said.

‘Am I?’

‘Your daddy went to the bank today.’

‘I know. But he says he’s not sure it’s going to happen. They might not give him the thing he needs.’

‘The mortgage,’ the little girl said patiently. ‘But they will.’

‘How do you know?’

‘He’s a famous writer, isn’t he? He’s good at making things up.’ She looked at the picture he was drawing and smiled to herself. ‘Just like you.’

Jake wondered about the smile. It was a strange one, as though she was happy but also sad about something. Come to think of it, that was how he felt about moving too. He didn’t like it in the house any more, and he knew it was making Daddy miserable too, but moving still felt like something they maybe shouldn’t do, even though he was the one who’d spotted the new house on Daddy’s iPad when they were looking together.

‘I’ll see you after I move, won’t I?’ he said.

‘Of course you will. You know that you will.’ But then the little girl leaned forward, speaking more urgently. ‘Whatever happens, though, remember what I told you. It’s important. You have to promise me, Jake.’

‘I promise. What does it mean, though?’

For a moment, he thought she might be about to explain it some more, but then the buzzer went on the far side of the room.

‘Too late,’ she whispered. ‘Your daddy’s here.’

Four

Most of the children seemed to be playing outside the 567 Club when I arrived. I could hear the mingled laughter as I parked up. They all looked so happy – so normal – and for a moment my gaze moved between them, searching for Jake, hoping to see him amongst them.

But of course, my son wasn’t there.

Instead, I found him inside, sitting with his back to me, hunched over a drawing. My heart broke a little at the sight of him. Jake was small for his age, and his posture right then made him seem tinier and more vulnerable than ever. As though he was trying to disappear into the picture in front of him.

Who could blame him? He hated it here, I knew, even if he never objected to coming or complained about it afterwards. But it felt like I had no choice. There had been so many unbearable occasions since Rebecca’s death: the first haircut I had to take him to; ordering his school clothes; fumbling the wrapping of his Christmas presents because I couldn’t see properly through the tears. An endless list. But for some reason, the school holidays had been the hardest. As much as I loved Jake, I found it impossible to spend all day, every day with him. It didn’t feel like there was enough left of me to fill all those hours, and while I despised myself for failing to be the father he needed, the truth was that sometimes I needed time to myself. To forget about the gulf between us. To ignore my growing inability to cope. To be able to collapse and cry for a while, knowing he wouldn’t walk in and find me.

‘Hey, mate.’

I put my hand on his shoulder. He didn’t look up.

‘Hi, Daddy.’

‘What have you been up to?’

‘Nothing much.’

There was an almost imperceptible shrug under my hand. His body seemed barely there, somehow even lighter and softer than the fabric of the T- shirt he was wearing.

‘Playing with someone a bit.’

‘Someone?’ I said.

‘A girl.’

‘That’s nice.’ I leaned over and looked at the sheet of paper. ‘And drawing too, I see.’

‘Do you like it?’

‘Of course. I love it.’

I actually had no idea what it was meant to be – a battle of some kind, although it was impossible to work out which side was which, or what was going on. Jake very rarely drew anything static. His pictures came to life, an animation unfolding on the page, so that the end result was like a film where you could see all the scenes at once, superimposed on top of each other.

He was creative, though, and I liked that. It was one of the ways in which he was like me: a connection we had. Although the truth was that I’d barely written a word in the ten months since Rebecca died.

‘Are we going to move to the new house, Daddy?’

‘Yes.’

‘So the person at the bank listened to you?’

‘Let’s just say that I was convincingly creative about the parlous state of my finances.’

‘What does “parlous” mean?’

It was almost a surprise that he didn’t know. A long time ago, Rebecca and I had agreed to talk to Jake like an adult, and when he didn’t know a word we’d explain it to him. He absorbed it all, and often came out with strange things as a result. But this wasn’t a word I wanted to explain to him right now.

‘It means it’s something for me and the person at the bank to worry about,’ I said. ‘Not you.’

‘When are we going?’

‘As soon as possible.’

‘How will we take everything?’

‘We’ll hire a van.’ I thought about money, and fought down a hint of panic. ‘Or maybe we’ll just use the car – really pack it up and do a few trips. We might not be able to take everything with us, but we can sort through your toys and see what you want to keep.’

‘I want to keep all of them.’

‘Let’s see, eh? I won’t make you get rid of anything you don’t want to, but a lot of them are very young for you now. Maybe another little boy would like them more.’

Jake didn’t reply. The toys might have been too young for him to play with, but each of them had a memory attached. Rebecca had always been better at everything with Jake, including playing with him, and I could still picture her, kneeling down on the floor, moving figures around. Endlessly, beautifully patient with him in all the ways I found it so hard to be. His toys were things she’d touched. The older they were, the more of her fingerprints would be on them. An invisible accumulation of her presence in his life.

‘Like I said, I won’t make you get rid of anything you don’t want to.’

Which reminded me of his Packet of Special Things. It was there on the table beside the drawing, a worn leather pouch, about the size of a hardback book, which zipped shut around three of the sides. I had no idea what it had been in a previous life. It looked like a large Filofax without the pages, although God knew why Rebecca would have had one of those.

A few months after she died, I went through some of her things. My wife had been a lifelong hoarder, but a practical one, and many of her older possessions were stored in boxes, stacked in the garage. One day, I’d brought some in and started to look through them. There were things going back to her childhood in there, entirely unconnected to our life together. It felt like that should have made the experience easier, but it didn’t. Childhood is – or should be – a happy time, and yet I knew these hopeful, carefree artefacts had an unhappy ending. I began crying. Jake had come and put his hand on my shoulder, and when I hadn’t immediately responded, he’d wrapped his small arms around me. After that, we’d looked through some of the things together, and he’d found what was to become the Packet and asked me if he could have it. Of course he could, I said. He could have anything he wanted.

The Packet was empty at that point, but he began to fill it. Some of the things inside had been sifted from Rebecca’s possessions. There were letters and photographs and tiny trinkets. Drawings he’d done, or items of importance to him. Like some kind of witch’s familiar, the Packet rarely left his side and, except for a few things, I didn’t know what was in there. I wouldn’t have looked even if I’d been able to. They were his Special Things, after all, and he was entitled to them.

‘Come on, mate,’ I said. ‘Let’s get your things and get out of here.’

He folded up the drawing and handed it to me to carry. Whatever the picture was meant to be, it clearly wasn’t important enough to go into the Packet. He picked that up himself and carried it across the room to the door, where his water bottle was hanging on a hook. I pressed the green button to release the door, then glanced back. Sharon was busying herself with the washing- up.

‘Do you want to say goodbye?’ I asked Jake.

He turned around in the doorway, and looked sad for a moment. I was expecting him to say goodbye to Sharon, but instead, he waved at the empty table he’d been sitting at when I arrived.

‘Bye,’ he called over. ‘I promise I won’t forget.’

And before I could say anything, he ducked out under my arm.

Five

On the day Rebecca died, I had picked Jake up by myself.

That afternoon was supposed to have been one of my writing days, and when Rebecca had asked if I could pick Jake up instead of her, my first reaction had been one of annoyance. The deadline for my next book was a handful of months away, and I’d spent most of the day failing miserably to write, at that point counting on a final half-hour of work to deliver a miracle. But Rebecca had looked pale and shaky, and so I had gone.

On the drive back, I had done my best to question Jake about his day, to absolutely no avail. That was standard. Either he couldn’t remember, or he didn’t want to talk. As usual, it had felt like he would have responded to Rebecca, which, coupled with the ongoing failure of the book, had made me feel more anxious and insecure than ever. Back home, he had been out of the car like a flash. Could he go and see Mummy? Yes, I had told him. I was sure she’d like that. But she wasn’t feeling well, so be gentle with her – and remember to take your shoes off, because you know Mummy hates mess.

And then I had dawdled at the car a little, taking my time, feeling bad about what an abject failure I was. I’d trailed in slowly, putting stuff down in the kitchen – and noting that my son’s shoes had not been taken off and left there as I’d requested. Because, of course, he never listened to me. The house was silent. I presumed that Rebecca was lying down upstairs, and that Jake had gone up to see her, and that everyone was fine.

Apart from me.

It was only when I finally went into the living room that I saw Jake was standing at the far end, by the door that led to the stairs, staring down at something on the floor that I couldn’t see. He was completely still, hypnotized by whatever he was looking at. As I walked slowly across to him, I noticed he was not motionless at all, but shaking. And then I saw Rebecca, lying at the bottom of the stairs. Everything was blank after that. I know I moved Jake away. I know I phoned for an ambulance. I know I did all the correct things. But I can’t remember doing them. The worst thing was that, although he would never talk to me about it, I was sure Jake remembered everything.

Ten months later, we walked in together through a kitchen where the surfaces were all but covered with plates and cups, the little visible counter space dirty with smears and crumbs. In the front room, the toys spread over the bare floorboards looked scattered and forgotten. For all my talk of sorting toys before we moved, it looked like we’d already gone through all our possessions, taken what we needed, and left the rest dotted around like rubbish. There had been a constant shadow over the place for months now, always growing darker, like a day gradually drawing to an end. It felt like our home had started falling apart when Rebecca died. But then, she had always been the heart of it.

‘Can I have my picture, Daddy?’

Jake was already on his knees on the floor, gathering his coloured pens together from wherever they’d rolled this morning.

‘Magic word?’

‘Please.’

‘Yes, of course you can.’ I put it down beside him. ‘Ham sandwich?’

‘Can I have a treat instead?’

‘Afterwards.’

‘All right.’

I cleared some space in the kitchen and buttered two slices of bread, then layered three slices of ham into the sandwich and sliced it into quarters. Trying to fight through the depression. One foot in front of the other. Keep moving.

I couldn’t help thinking about what had happened at the 567 Club: Jake waving goodbye to an empty table. For as long as I could remember, my son had had imaginary friends of some kind. He’d always been a solitary child; there was something so closed off and introspective about him that it seemed to push other children away. On good days, I could pretend that it was because he was self-contained and happy in his own head, and tell myself that was fine. Most of the time, I just worried.

Why couldn’t Jake be more like the other children?

More normal?

It was an ugly thought, I knew, but it was only because I wanted to protect him. The world can be brutal when you’re as quiet and solitary as he was, and I didn’t want him to go through what I had at his age.

Regardless, until now the imaginary friends had manifested themselves subtly – more like little conversations he’d sometimes have with himself – and I wasn’t sure I liked this new development. I had no doubt the little girl he told me he’d been talking to all day had existed only in his head. This was the first time he’d acknowledged something like that out loud, talking to someone in front of other people, and that scared me slightly.

Of course, Rebecca had never been concerned. ‘He’s fine – just let him be him.’ And since she knew better than me about most things, I’d always done my best to abide by that. But now? Now, I wondered if maybe he needed real help.

Or maybe he was just being him.

It was one more overwhelming thing that I should have been able to deal with, but didn’t know how. I didn’t know what the right thing to do was, or how to be a good father to him. God, I wished that Rebecca was still here.

I miss you . . .

But that thought would make the tears come, so I cut it dead and picked up the plate. As I did so, I heard Jake speaking quietly in the front room.

‘Yes.’ And then, in answer to something I couldn’t hear, ‘Yes, I know.’

A shiver ran through me.

I walked quietly over to the doorway, but didn’t step through it yet – just stood there listening. I couldn’t see Jake, but the sunlight through the window at the far end of the room was casting his shadow across the side of the settee: an amorphous shape, not recognizably human but moving gently, as though he was rocking back and forth on his knees.

‘I remember.’

There were a few seconds of silence then, in which the only sound was my own heartbeat. I realized I was holding my breath. When he spoke next, it was much louder, and he sounded upset.

‘I don’t want to say them!’

And at that, I stepped through the doorway.

For a moment, I wasn’t sure what I was going to see. But Jake was crouched down on the floor exactly where I’d left him, except that now he was staring off to one side, his drawing abandoned. I followed his gaze. There was nobody there, of course, but he seemed so intent on the empty space that it was easy to imagine a presence in the air.

‘Jake?’ I said quietly.

He didn’t look at me.

‘Who were you talking to?’

‘Nobody.’

‘I heard you talking.’

‘Nobody.’

And then he turned slightly, picked his pen back up and started drawing again. I took another step forward.

‘Can you put that down and answer me, please?’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s important.’

‘I wasn’t talking to anybody.’

‘Then how about putting the pen down because I said so?’

But he kept drawing, his hand moving more fervently now, the pen making desperate circles around the little figures there.

My frustration curdled into anger. So often, Jake seemed like a problem I couldn’t solve, and I hated myself for being so useless and ineffective. At the same time, I also resented him for never offering me so much as a clue. Never meeting me halfway. I wanted to help him; I wanted to make sure he was okay. And it didn’t feel like I could do that by myself.

I realized I was gripping the plate too tightly.

‘Your sandwich is ready.’

I put it down on the settee, not waiting to see if he stopped drawing or not. Instead, I went straight back through to the kitchen, leaned on the counter there and closed my eyes. For some reason, my heart was pounding.

I miss you so much, I thought to Rebecca. I wish you were here. For so many reasons, but right now because I don’t think I can do this.

I started to cry. It didn’t matter. Jake would either be drawing or eating his tea for a while, and he wasn’t going to come through. Why would he, when there was only me through here to see? So it was fine. My son could talk quietly to people who didn’t exist for a while. As long as I was equally quiet, so could I.

I miss you.

That night, as always, I carried Jake up to bed. It had been that way ever since Rebecca’s death. He refused to look at the place where he had seen her body, clinging to me instead, with his breath held and his face buried in my shoulder. Every morning, every night, every time he needed the bathroom. I understood why, but he was beginning to grow too heavy for me, in more ways than one.

Hopefully that would change soon.

After he was asleep, I went back downstairs and sat on the settee with a glass of wine and my iPad, loading up the details of our new house. Looking at the photograph on the website made me uneasy on a different level.

It was safe to say it was Jake who had chosen this house. I hadn’t been able to see the appeal at first. It was a small, detached property – old, two storeys, with the ramshackle feel of a cottage. But there was something a little strange about it. The windows seemed oddly placed, so that it was hard to imagine the layout inside, and the angle of the roof was slightly off, so that the face of the building appeared to be tilted inquisitively, perhaps even angrily. But there was also a more general sensation – a tickling at the back of the skull. At first glance, the house had unnerved me.

And yet, from the moment Jake had seen it, he had been set on it. Something about the house had utterly entranced him, to the point that he refused to look at any others.

When he’d accompanied me to the first viewing, he had seemed almost hypnotized by the place. I had still not been convinced. The interior was a good size, but also grimy. There were dusty cabinets and chairs, bundles of old newspapers, cardboard boxes, a mattress in the spare room downstairs. The owner, an elderly woman called Mrs Shearing, had been apologetic; this all belonged to a tenant she had been renting to, she explained, and would be gone by the time it was sold.

But Jake had been adamant, and so I’d organized a second viewing, this time by myself. That was when I had started to see the place with different eyes. Yes, it was odd-looking, but that gave it a sort of mongrel charm. And what had initially felt like an angry look now seemed more like wariness, as though the property had been hurt in the past and you’d have to work to earn its trust.

Character, I supposed.

Even so, the thought of moving terrified me. In fact, there had been a part of me that afternoon that had hoped the bank manager would see through the half-truths I’d told about my financial situation and just turn down the mortgage application outright. I was relieved now, though. Looking around the front room at the dusty, discarded remnants of the life we’d once had, it was obvious that the two of us couldn’t continue as we were. Whatever difficulties lay ahead, we had to get out of this place. And however hard it was going to be for me over the coming months, my son needed this. We both did.

We had to make a fresh start. Somewhere he wouldn’t need to be carried up and down the stairs. Where he could find friends that existed outside his head. Where I didn’t see ghosts of my own in every corner.

Looking at the house again now, I thought that, in a strange way, it suited Jake and me. That, like us, it was an outsider that found it hard to fit in. That we would go together well. Even the name of the village was warm and comforting.

Featherbank.

It sounded like a place where we would be safe.

The Whisper Man Alex North

Gripping, moving and brilliantly creepy, this is an outstanding new psychological thriller

Buy now