- Published: 28 August 2017

- ISBN: 9781925324105

- Imprint: Random House Australia

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 464

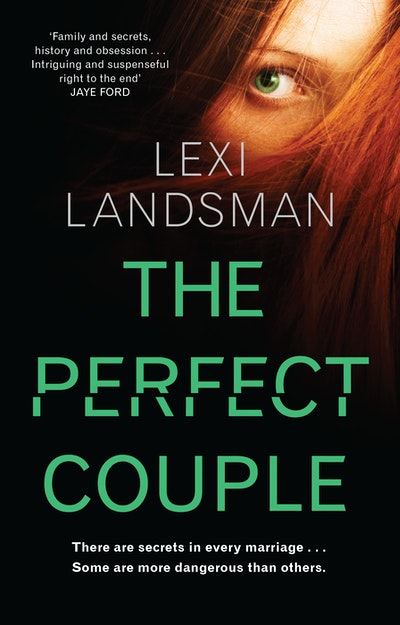

The Perfect Couple

Extract

So, when I was on archaeological excavation sites like the one in Florence, that desire drove me, pushed me through the unrelenting heat, the often claustrophobic trenches and the long days. I wanted to be the one to find what my predecessors couldn’t.

It was close to midday and, being the middle of July, the sun was potent. It felt like an eye, watching us, beating down on our heads and the back of our necks, blistering any uncovered skin. I had deliberately scheduled the recording during the team’s siesta so I wouldn’t have any distractions during my televised interview. My wife, however, stayed behind to watch the filming.

‘Doctor Moretti, five minutes until we’re live on air,’ the television producer said. He was standing behind a silver circular reflector, with a notepad in hand, squinting into the sun. The popular cultural TV show Italy Uncovered wanted to do the interview live on the excavation site. This was exactly the type of exposure I was hoping for.

The humidity was making me sweat incessantly. A make-up artist stepped forward and dabbed my oily forehead with powder. The presenter, Tarea Soretto, was sitting in front of me scanning her questions and then using her notepad as a fan over her face. ‘You’re going to be great,’ she said to me and smiled in that artificial journalist way. Perhaps she mistook my sweating for nerves. I almost laughed – if only she knew how much I relished these televised interviews. I felt more at ease in front of the camera than I did almost anywhere else.

Tarea had been a news reporter and host for twenty-five years, and was something of a legend in Italy. She was wearing a tight-fitting red dress with cropped sleeves, revealing her surprisingly toned arms. She looked pretty good for a woman in her early fifties, but even though I was forty-five, she was far too old to be my type.

The sound recordist did a final adjustment of my lapel mic and then returned to his position next to one of the cameramen. He called out ‘Rolling,’ and Tarea sat upright, staring down the lens of the camera, her whole demeanour livening.

‘Welcome to Italy Uncovered. We’re live today in Florence on the excavated courtyard of a medieval castle with Doctor Marco Moretti, a real-life Indiana Jones. He’s a historian and archaeologist who recently made headlines with the astounding claim that the famed San Gennaro necklace – thought to have been lost at sea in the late 1700s – may, in fact, be buried right here, metres below ground level.’ She turned to me, her dark brown eyes penetrating. ‘So, Doctor Moretti, tell us about the San Gennaro necklace and your remarkable theory.’

‘Thank you for having me on the show, Tarea.’ I smiled. ‘As you know, the necklace of San Gennaro – or Saint Januarius as it’s known in English – was part of a collection of lavish gifts honouring San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples, in return for his protection from epidemics, earthquakes, plagues and the dreaded Mount Vesuvius. The necklace was made in 1679 by goldsmith Michele Dato. Thirteen gold links form the base of the necklace, which was continually added to by royals, emperors and aristocrats so that by the time it was supposedly lost at sea, it was recorded as having seven hundred diamonds, two hundred and seventy-six rubies and ninety-two emeralds.’

Tarea knew this information but she widened her eyes as if it were a surprise. ‘What would you estimate the necklace to be worth if it were found today?’

‘It would be the most valuable piece of religious jewellery in existence. A remarkable chain of Italian history.’ I spoke slowly now for impact. I’d done enough of these interviews to know how to work the camera. ‘So, if I were to put a figure on it, I’d say it would be somewhere in the vicinity of one hundred and fifty million euros.’

She gasped, and I had no doubt that the second camera positioned behind me had reframed to get a close-up of her awestruck expression.

Tarea shook her head in disbelief. ‘Wow. That’s incredible. To understand the value of the necklace, take us back to the late 1700s when Napoleon Bonaparte was at the height of his powers. Is it not true that before departing on his first Italian campaign, he assigned four renowned artists to join the French army, with the goal of collecting monuments of arts and sciences when they looted Italian museums?’

‘That’s right. In 1796, the army entered the north of Italy, pushing down the Italian peninsula. As they moved they stole classical artefacts and Renaissance works of art, which were later displayed in museums across France.’

‘As they continued south, were the people of Naples fearful for the San Gennaro treasure?’

Her questions were feeding perfectly into my somewhat rehearsed speech. ‘Absolutely. In December of 1798, the French army was marching towards Naples. The royal family was planning to flee Naples, which they kept a closely guarded secret, fearing a revolt. The priest of Naples Cathedral grew increasingly fearful that the royals would soon come to seize the San Gennaro necklace, and he was right. Before the French arrived, King Ferdinand of Naples and his wife Maria Carolina commanded he hand it over. They loaded the English ship Colossus with the precious jewel along with British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples Sir William Hamilton’s collection of extremely valuable antiquities that were to be sent to England.’

‘So, what happened?’

‘The monarchs fled Naples on another ship, setting sail on Christmas Eve. However, news soon arrived that while the monarchs had reached safety in Sicily, the Colossus had sunk in a storm off the Scilly Isles near England. The San Gennaro necklace was lost at sea.’

Tarea narrowed her eyes, a look of concern on her face.

‘And so for more than two hundred years, it was believed to have been lost forever,’ I continued. ‘In 1974, explorers and ocean archaeologists scaled the sea floor near the Isles of Scilly searching for the necklace. They found the box the necklace was kept in, but it was empty. The necklace was never found.’

‘This brings us to your compelling assertion that the neck lace was never lost at sea and might be right here, buried under our feet. How did you come to that theory?’

‘During my PhD studies I came across the San Gennaro jewellery box that was found at sea, along with letters the Neapolitan priest received from a loyal acolyte. I studied the box closely – and I realised it was a replica. The genuine box that the necklace was stored in during the eighteenth century was made using the technique of pietre dure inlay, which used multicoloured polished precious and semiprecious stones cut and fitted with such precision that the lines of contact between each stone are invisible, creating the impression of a painting on stone. Drawings of this particular ebony box reveal that it had scrolling leaves and an image of the saint surrounded by rectangular slate plaques framed in red marble. But I soon realised that the box found on the ocean floor was actually created using a technique called scagliola, a sort of poor man’s pietre dure in that it resembles inlays of marble and semiprecious stones but is actually made from a composite substance of selenite, glue and natural pigments that imitate marble and other hard stones.

‘Once I knew for certain it was a fake, I returned to the letters. I ascertained from my lengthy study of them that the priest had a trustworthy source within the palace, and when the monarchs started collecting treasures to take with them as the French army closed in, the priest must have commissioned one of the finest scagliola artists to create a replica of the box in which the San Gennaro necklace was kept. He knew that if he let the necklace go with the royal family, the people of Naples would never see it again. On the eve of their departure, the priest’s acolyte replaced the pietre dure box with the empty replica.’

‘So, if your theory is right, what really happened to the necklace?’

Each time I reveal my discovery, I get a rush through my body that makes me feel electric. ‘The letters were sent to the priest from his acolyte, who spoke of his new life in Florence. He described where he was living in great detail – a castle on a hill in Fiesole.’ I stop and gesture with my hands to the site around me. ‘This very castle. When I examined them closely, putting all the letters together, I realised that each one was leaving a coded clue to the necklace’s hiding place. He wrote things such as I am safe here. There are no windows in my room as I sleep below the castle floor. And in another, I yearn to return to my true home of Naples and will await your instruction as to when it is safe to do so.

‘But the fate of the necklace was to be dealt another cruel blow, wasn’t it, when in 1805 a catastrophic fire destroyed a large section of the castle, burying with it the secret of the necklace?’

‘In the last letter, obviously written in haste, the priest’s loyal follower described how the fire destroyed an entire wing of the castle. He had been badly burned and didn’t think he would survive. He had no time to write in code and it was the only letter in which he referred to the necklace. His last words were: Our precious jewel is buried within the castle ruins. I do pray that it will one day return to its rightful home.’

Tarea maintained her steady gaze and appeared completely mesmerised. ‘And what became of the castle?’ she asked animatedly, genuine intrigue clear in her voice.

‘The castle was later purchased by an English expatriate, who spent twelve years redesigning it in Victorian Gothic Revival style. Over the wing that had been destroyed by the fire, he built a courtyard, and so it remained.’

‘And here we are now. The excavation is in full swing. And if your theory is right, any day now, you might hit gold,’ she said, her eyes glinting.

‘It would be an enormous find, not only for the people of Italy, but for all of Europe. Each stone tells a story. It’s a remarkable chain of our history.’

After the television crew had left, I felt invigorated by what I knew was an exceptional interview. I’d certainly done a good enough job to arouse even more interest in our excavation.

I had four teams of six working across the trenches, plus a full-time conservator back in the sheds. We called in specialists whenever they were needed.

The workers had returned from their siesta for the afternoon session, which was usually spent cleaning any new finds. We would wash any pottery fragments, what we called sherds, and record any found artefacts onto a database. Once everything was cleaned and processed, we would label and store them. The team had been working for the past hour under the blazing sun. ‘You can go home early today,’ I told them. ‘This heat is insufferable.’

It wasn’t so much their welfare I cared about. As the field director, the most senior figure on site, I would sooner have them work through the night if it meant finding something of value. But all I could think about was escaping the heat and going for a swim.

Carlos, who like me had dark olive skin from a lifetime spent under the European sun, turned to me, relief in his brown eyes. ‘Thank you, Marco,’ he said standing and stretching.

‘My mother says it’s the hottest July she’s ever known in Florence,’ Sofia said. She was one of the youngest on the team at twenty-eight, and incredibly attractive.

Even though I’m a married man, younger women have always had an effect on me. I met my wife Sarah two decades ago when we were both studying for a PhD in archaeology at Cambridge University. We were assigned together in a group research study in medieval artefacts. I wouldn’t say we hit it off straightaway. In fact, it was quite the opposite. Sarah was opinionated and didn’t like to lose an argument. I was used to women lusting after me thanks to my good looks and intellect, and hanging on to my every word, something I used in my favour during my undergraduate degree in Florence. Sarah wasn’t like that. She would argue any theory I put forward and seemed to get a rush out of proving that she was smarter, that she was one step ahead of me. I admired her strong-headed nature.

Of course, it helped that she was not only smart but beautiful in an unusual and arresting way. For some reason when my eyes first fell on her, she reminded me of the depiction of Venus in the famous artwork, Birth of Venus, by renowned Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli. Maybe it was her pale flawless skin or her long hair, which was a shade between red and a sort of orange-blonde, or perhaps it was the sense of mystique that shrouded her. She had a warm smile, high cheekbones and pale green eyes, the colour of water in a shallow stream, but with a dark green midnight rim.

I guess you could say we were opposites in almost every way. She was an Australian from a warm family who lived comfortably and I was a dark-skinned and often dark-tempered Italian whose upbringing was one of neglect and poverty. Then there were the little things – she had a love of coffee, I detested it; she hated to swim, I couldn’t last more than a few days without taking a cool dip; she loathed being in the public eye, I relished it. And yet, despite our contradictions, we worked like different shapes of a jigsaw puzzle that fit perfectly together. She filled my broken edges. Our friends and colleagues often remarked that we were the perfect couple and I often got the feeling that their words were tinged with jealousy.

I gazed over at Sarah now as she wiped a film of dirt off her cheek. She was wearing a long-sleeved beige shirt and loose khaki pants, her slim figure hidden underneath the baggy clothes. No one ever looked particularly glamorous in this line of work, except of course for Sofia, who exuded effortless elegance.

Sarah looked up at me just as my gaze fell on the slipped bra strap resting on Sofia’s bare shoulder, glistening in the sun as if beckoning. Sarah cast her eyes back down again, regaining her steely focus.

Even though my wife was no longer turned in my direction, it felt as though she was watching me. That was the problem with working alongside her. I could never let my guard down. It the only downside to what was, otherwise, a faultless working partnership.

While my team packed up their tools, I realised that I’d barely said a word to Sarah all day, despite the fact that we worked within a twenty-metre radius. She was the trench supervisor, the level below me on the site hierarchy. She was quietly authoritative without being overbearing and although she was an exceptionally hard worker, she always made time for everyone, which is perhaps why the team all seemed to admire her.

Sarah continued to plunge her handpick into the soil, seemingly unperturbed by the heat. ‘You’re staying?’ I asked.

She wiped a strand of hair from her damp forehead, locking her eyes on me. ‘I’m not ready to pack up.’

She said it in that tone of old, as if she were trying to prove that her resolve was stronger than mine. But the beads of sweat around her neck and above her lip told me otherwise.

‘Suit yourself,’ I said. I was long past defending my work ethic. ‘I’m off to swim at Le Pavoniere pool. If you change your mind, that’s where you’ll find me.’

In what felt like another lifetime, we could barely keep our hands off each other. We would sneak kisses on excavation sites when the others looked away. We would exchange glances across a full lecture hall and escape early to each other’s rooms. I remember running my hands over the pale skin of her body, her white flesh, unblemished, untouched by anyone else’s hands, or so I told myself. I felt like her guardian and protector, her body an offering meant only for me. I would make a mental map as I felt her breasts, her torso, her thighs. I couldn’t get enough of her.

She used to coil her body around mine and tell me she didn’t want to picture her life before us. It was the only history, she had said, that wasn’t worth revisiting. We were so in love that I never contemplated that my desire for her could fade.

‘Enjoy the swim,’ she said.

I pecked her on the cheek. Perfunctory. She smiled faintly and looked back down, picking up her brush to dust away the dry sand.

I turned back as I reached the scaffolding surrounding the excavation site and watched her, the lone archaeologist left on the vast grounds. How small she looked. How focused and deep in thought. Even after more than twenty-two years, two children and two decades of travelling and working together, there was so still much about my wife I didn’t know. Maybe that’s why I had fallen for her all those years ago … because her mind was a mystery to me; like an ancient codex I couldn’t decipher.

Le Pavoniere was an outdoor pool set in the largest park of the city, Parco delle Cascine, which ran along the Arno River. I went there often to cool off but avoided it on the weekends when it was overrun with children.

There was barely a breath of wind. The pool was packed, which was unsurprising given the heat and the few places there were to swim in the city.

The sun lounges were all taken, so I put my towel down and took off my sweat-soaked shirt and trousers, and changed into swimming trunks. I always did laps of the pool for cardio along with running a few times a week with my sixteen-year-old daughter, so I was fit for my age. I took pride in my appearance and made sure that every morning I did a thirty-minute abdominal workout, which kept my stomach firm and toned, although, admittedly not like the carved six-pack I had in my youth.

I dove into the pool. The water rushed over me like an embrace. My mind was so occupied with thoughts of the necklace that when I looked up to the surface of the water, the refracting light made it appear as though it were sprinkled with diamonds. When I came up for air, I turned onto my back and floated with my eyes closed, imagining what it would feel like to see and hold the San Gennaro necklace in my hands – the fire and sparkle of each diamond, the brilliant blues of the sapphires, the vivid emeralds. I thought of the fame that would come to me if I ever found it. The most valuable piece of religious jewellery in the world. The greatest archaeological discovery of the century. And how my name would be emblazoned in history.

I wanted it more than anything I had ever wanted in my life. And I knew I would stop at nothing to get it.

The Perfect Couple Lexi Landsman

In this suspense novel, which will appeal to fans of Gone Girl, it's clear that the truth is not always what it seems . . .

Buy now