- Published: 2 March 2021

- ISBN: 9780552176583

- Imprint: Corgi

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 416

- RRP: $22.99

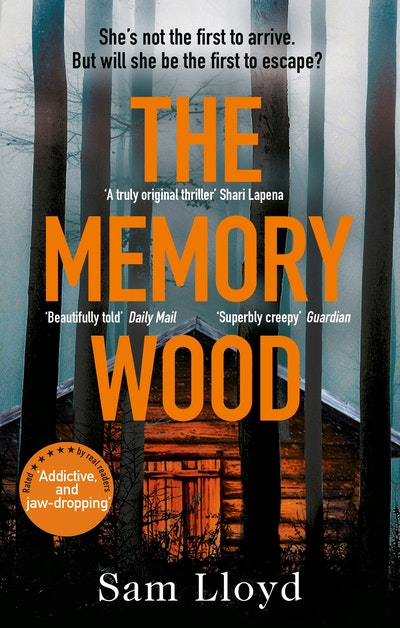

The Memory Wood

Extract

PART I

ELIJAH

Day 6

I

When they file back into the room, I’m no longer in the chair. Instead, I’m sitting on the table, bare legs swinging. A pink square of sticking plaster gleams on my knee. Weird, really, that I don’t remember injuring it.

They raise their eyebrows when they see I’ve moved, but nobody comments. The table is bolted to the floor so it can’t tip over and hurt me. When I was ten, I broke my leg running in the Memory Wood and nearly died, but that was two years ago. I’m much more careful now.

‘Seems like we’re all done, Elijah,’ one of them says. ‘Are you looking forward to going home?’

I glance around the room. For the first time I notice it has no windows. Maybe that’s because of the sort of people it usually contains – bad people, not like these in here with me now. They’re police, even if they don’t wear the uniforms. Earlier, the one who brought me a Coca-Cola told me they wear play clothes. He could have been joking. For a twelve-year-old I have a pretty high IQ, but I’ve never really understood teasing.

For a moment I forget they’re still watching me, still waiting for an answer. I glance up and nod, swinging my legs harder. Why wouldn’t I be looking forward to going home?

My face changes. I think I’m smiling.

II

We’re in the car. Papa is driving. Magic Annie, who lives on the far side of the Memory Wood, says that these days most kids call their parents Mum and Dad. I’m pretty sure I used to do that too. I don’t really know why I switched to Mama and Papa. I read a lot of old books, mainly because we don’t have money to waste on the newer stuff. Maybe that’s it.

‘Did they question you?’ Papa asks.

‘About what?’

‘Oh, about anything, really.’

He slows the car at a crossroads, even though he has right of way. Always careful like that, is Papa. Always worried that he’ll hit a cyclist or a dog-walker, or a slow-crossing hedgehog.

‘They asked me about you,’ I say.

In the front seat, Mama turns to look at him. Papa’s attention remains on the road. He holds the steering wheel delicately, wrists angled higher than his knuckles. It makes him look like a begging dog, and suddenly I think of the Arthur Sarnoff print that hangs on our living-room wall, of a beagle playing pool against a couple of rascally, cigarchomping hounds. The picture’s called Hey! One Leg on the Floor! because the beagle is perched on a stepladder, which is cheating. Mama hates it, but I kind of like it. It’s the only picture we have.

‘What did they ask you?’

‘Oh, you know, Papa, just stuff. What kind of job you do, what kind of hobbies you have, that sort of thing.’ I decide not to mention their other questions just yet, nor my answers. Not until I’ve had a bit more time to think. In the last few days a lot’s happened, and I need to get it all straight. Sometimes life can be pretty confusing, even for a kid with a high IQ.

‘What did you tell them?’

‘I said you’re a gardener. And that you fix things.’ I make a dimple in the pink plaster on my knee and wince. ‘I told them about the crow you saved.’

We found the crow outside the back door one morning, flapping a broken wing. Papa nursed it for three days straight, feeding it bread soaked in milk. On the fourth day we came downstairs to find it gone. Crow bones, Papa said, mend much faster than human ones.

III

We’re coming to the edge of town. Fewer buildings, fewer people. On the pavement I see two boys wearing uniform: grey trousers, maroon blazers, scuffed black shoes. They look about my age. I wonder what it must be like to have lessons at school instead of at home. There isn’t a book in my house I haven’t read ten times over, so I’m pretty sure I’d do well. Magic Annie says I have the vocabulary of someone with far bigger shoes. There was a playwright, once, who knew sixty thousand words. I’d like to beat him if I can.

As we speed past, I press my palm against the window. I imagine the boys turning and waving. But they don’t, and then they’re gone.

‘Did you talk about me?’ Mama asks.

Her head is still sideways. I’m struck by how pretty she looks today. When the low sun breaks through the clouds her hair gleams like pirate gold. She looks like an angel, or one of those warrior queens I’ve read about: Boudicca, perhaps, or Artemisia. I want to climb into the front seat and curl up in her lap. Instead, I roll my eyes in mock-exasperation. ‘I’m not a complete witling. Just because I got lost this one time.’

Witling is my new favourite word. Last week it was flibbertigibbet, which is Middle English for an excessively chatty person. Everyone’s life should contain a couple of flibbertigibbets, preferably with a few witlings to keep them company.

Again, I glance out of the window. This time all I see is fields. ‘I hope Gretel’s OK.’

‘Gretel?’ Papa asks.

Immediately, I get a funny feeling in my tummy; a greasy slipperiness, like there’s a snake inside me, coiling and uncoiling. Gretel, I remember, is a secret. I look up and meet Papa’s eyes in the rear-view mirror. His brow is furrowed. My hands begin to shake.

I glance at Mama. A pulse beats in her throat. ‘There is no Gretel, Elijah,’ she says. ‘I thought you understood that.’

In my tummy, more of the snake uncurls. ‘I . . . I mean Magic Annie,’ I stammer, my words rushing out. ‘It’s my play name for her. A thing I invented. Just a silly thing.’

Papa’s eyes float in the mirror. ‘I think Magic Annie suits her better than Gretel,’ he says. ‘Don’t you, buddy?’

My mouth tastes sour, like I’ve bitten down on a beetle or a toad. I run my tongue over my teeth and swallow. ‘Yes, Papa.’

IV

Our estate isn’t like those I’ve seen on Magic Annie’s TV. There are no high-rise blocks or rows of modern homes – only woods, fields, barns, cowsheds and the mansion called Rufus Hall. Dotted about the land are a few stone-built cottages, including our own. Tied cottages, they’re called.

Beyond the Memory Wood lies Knucklebone Lake. That’s not the lake’s real name – I don’t think it has one. It’s just that once, in the reeds lining the bank, I found a tiny trio of bones connected by rotting ligament. They looked like they might form the index finger of a small child. I put them in my Collection of Keepsakes and Weird Finds, a grand name for what’s really a Tupperware box hidden beneath the loose floorboard in my room.

Not far from the lake is the place I call Wheel Town. It’s more of a camp than anything else, a ragtag collection of trucks and caravans that were driven here long ago and are mostly too rusted up to leave. I’ve never worked out why the Meuniers tolerate the Wheel Town folk on their land, but they do.

The Meuniers live up at Rufus Hall. Just the two of them, knocking about with all that space. Leon Meunier spends most of his time in London. On the days he’s at the estate, I see him zooming about in his black Defender with a face like he’s worried the sky’s about to fall. The house and its gardens would be an awesome place to explore, but Papa won’t ever let me go.

Our car jerks to a stop. I realize we’re home. In the front seat, Mama bows her head. I wonder if she’s praying. Looking down, I see my hands have stopped trembling. I pop my seatbelt and grab the door handle, but of course I can’t get out. My parents still use the child locks, even though I’m twelve years old.

I wait for Papa to open the door. Then I worm out of my seat. He lumbers up the garden path, shoulders braced as if he’s carrying all the world’s troubles. Mama and I follow.

Our cottage windows are dark, offering no hint of what lies within. The front door is a single slab of oak. There’s no letterbox. Papa rarely gets any post, and when he does it’s delivered straight to Meunier. Mama gets nothing at all. Our door has no number, because we don’t live on a street. If anyone ever wrote to me, they’d have to put this on the envelope: Elijah North, Gamekeeper’s Cottage, C/O THE RT HON. THE LORD MEUNIER OF FAMERHYTHE, Rufus Hall, Meunierfields. That’s quite a lot to write, which explains why Mama isn’t the only one the postman ignores.

There’s an upside-down horseshoe nailed to the lintel, put there to catch us some luck. Passing beneath it, I go inside.

V

I’m in my room, standing at the window. We’ve been home twenty minutes. I’m itching to escape, but I daren’t, not yet.

When I hear the back door clatter open, I step closer to the glass. Down in the garden, Papa looms into view. He tugs a packet of Mayfairs from his chest pocket and lights up. Leaning against the coal shed, he breathes a fog of smoke into the sky. I go to the hall, creep down the stairs and out through the front door.

From our cottage, the Memory Wood is a five-minute walk. I make it in half that time, jogging along the track beside Fallow Field. Overhead, the sky presses down like a steel sheet. The day feels heavy, as if it might crumple under its own weight.

I’m halfway there when I hear the screaming. Twisting around, I see a family of crows squabbling in Fallow Field. Something’s got their interest – likely the remains of a rabbit or pheasant that a fox has left. The collective noun for crows, I once read, is murder.

Pretty gross.

The Memory Wood Sam Lloyd

Gripping, twisty and addictive, this unique and heart-wrenching thriller has received unprecedented support from readers, press and authors alike. The must-read thriller of the year.

Buy now