- Published: 14 December 2021

- ISBN: 9780552177603

- Imprint: Corgi

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 784

- RRP: $24.99

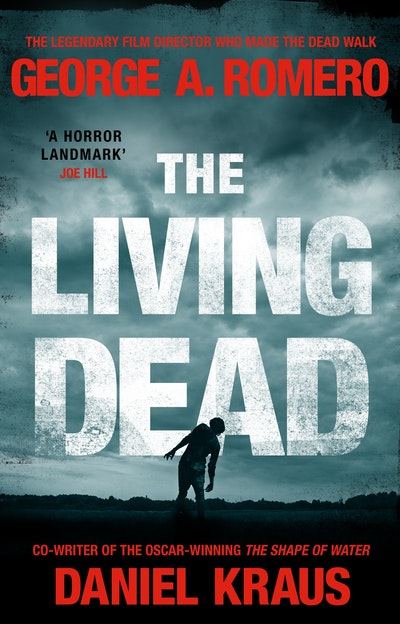

The Living Dead

A masterpiece of zombie horror

Extract

John Doe’s VSDC case number, 129–46–9875, was recognized by the system twice on the night he died: October 23. It was initially and unremarkably input by St. Michael the Archangel, a Catholic hospital in San Diego, California. The second entry, the one that made the case notable, came three and a half hours later from the Medical Examiner’s Office in San Diego County. It reached VSDC central computers at 10:36 p.m., Pacific standard time, but went unnoticed for another forty-eight hours, until a quiet, offish AMLD statistician named Etta Hoffmann found it while searching for abnormalities in recent files.

Hoffmann printed a hard copy of the record. Even then, she had a sense of foreboding about the systems upon which humans had come to depend.

No matter what program, typeface, or font size was originally used by an entrant, a default conversion was made, for the sake of standardization, by the VSDC system. John Doe’s file was spat from an AMLD printer in a font called Simplified Arabic. Years after the launch of VSDC, there had been a Senate spat over whether it was appropriate for a government agency to adopt a typeface designated as “Arabic.” The Democratic majority defeated the Republicans lobbying for Franklin Gothic. Upon prevailing, the Democrats indulged in satisfied winks and jolly backslaps.

None who survived the weeks after John Doe remembered this petty victory. It was but one of a million tiffs that had been tearing the country into pieces for generations. In the dark days to come, some former Congress members would wonder, if they’d only listened closer, if they might have heard America’s tendons pinging apart like snapped piano wire and been able to do something to heal the wounds before the whole body politic had been ripped apart.

Thousands of files sharing similarities with 129–46–9875 were received during the three days following John Doe’s death. Etta Hoffmann discovered John Doe’s file while trying to determine the starting point of the phenomenon. The VSDC system did not organize entries by date and time; the original designers hadn’t believed that function would be needed. Hoffmann and her coworkers had to search manually, and only later, when comparing the findings they’d thrown into a folder labeled Origin, did the time stamp on John Doe’s dossier indicate it preceded all others. She was not 100 percent confident of it, but at some point, even she had to stop searching.

There were other, more pressing matters.

By the end of that third night following John Doe’s death, only two men and two women remained at AMLD’s Washington office, clicking, scribbling, and filing. The quartet pulled together adjacent desks and worked in ragged, lopsided shift s, none more tirelessly, or with such enviable composure, as Etta Hoffmann.

Hoffmann had always been AMLD’s oddball. Every statistician forced to work with her presumed her personal life, like her work life, was full of leaden, blank-stare interactions.

Unlike Hoffmann, the other three lingerers had knowable reasons for staying. John Campbell’s recent years had been traumatic—the death of a child, a divorce he hadn’t wanted—and he had no one left to run to. Terry McAllister had gotten into government work with dreams of singlehandedly saving the day; he wasn’t going anywhere. Elizabeth O’Toole had a husband she feared, especially during stressful times, and the hope that this event could be her escape kept her bolted to her seat.

In addition, Terry McAllister and Elizabeth O’Toole were in love. Etta Hoffmann had figured that out some time before the crisis. She did not understand this. Both were married to other people. That was something Hoffmann understood. Marriage revolved around legal documents, co-owning property, and joint tax returns. Love and lust, though, had always been illogical puzzles to Hoffmann. They made the afflicted unpredictable. She was wary of Terry McAllister and Elizabeth O’Toole and gave them additional space.

Etta Hoffmann’s reason for staying? The others could only guess. Some at AMLD, miffed by Hoffmann’s lack of emotion, believed her stupid. Those aware of the staggering volume of work she did speculated she was autistic. Others thought she was simply a bitch, though even that gendered slur was suspect. Besides her first name and choice of restroom, there was little evidence of how Hoffmann identified. Her features and body shape were inconclusive, and her baggy, unisex wardrobe offered few clues. Watercooler speculation was that Hoffmann was trans, or intersex, or maybe genderqueer.

A temp worker, under the influence of his English major, once referred to Etta Hoffmann as “the Poet” because she reminded him of Emily Dickinson, pale and serious, gazing into the depths of a computer screen as Dickinson had gazed down from a cloistered berth. Perhaps Hoffmann, as inscrutable as Dickinson, found in everyday monotony the same sort of vast morsels.

The nickname served to excuse Hoffmann’s distant manner and deadpan replies. Such were the prerogatives of the Poet! Who could hope to understand the Poet’s mind? It was fun for the whole office. It attributed sweeping, romantic notions to an androgynous, sweatpants-wearing coworker who joylessly keyed data while drinking room- temperature water and eating uninspiring sandwiches assembled in what was undoubtedly the blandest kitchen in D.C.

During the three days after John Doe, the Poet proved herself the best of them all, stone-faced when others broke down, eyes quick and fingers nimble when others’ heavy eyelids slid shut and their hands trembled too much to type. Hoffmann, the least inspiring person anyone had ever met, inspired the other three holdouts. They dumped cold water on their heads and slapped their cheeks. Powered by cheap coffee and adrenaline, they recorded what was happening so that future denizens might find evidence of the grand, complicated, flawed-but-sometimes-beautiful world that existed before the fall.

Forty-eight hours later, five days after John Doe’s 129–46–9875 report, John Campbell, Terry McAllister, and Elizabeth O’Toole agreed that there was nothing more to be done. Although AMLD’s emergency power kept their office fully functional, the VSDC network was in collapse. The reports still dribbling in were little more than unanswerable cries for help. John Campbell shut down his computer, the black monitor reminding him of his lost child and lost wife, went home, and shot himself in the head. Elizabeth O’Toole began obsessively doing push-ups and sit-ups, preparation for an uncertain future. Terry McAllister, his dreams of heroism faded, made a final entry in his work log. It strayed from the usual facts and figures into something, should anyone ever find it, that might have read as gallows humor: “Happy Halloween.”

It was three days before that spooky holiday, three weeks before Thanksgiving, two months before Christmas. Millions of pieces of candy, instead of being doled out to trick-or-treating children, would become emergency rations for those too afraid to leave their homes. Those who bought Thanksgiving turkeys early would jealously hoard them instead of inviting loved ones over to share. Thousands of plane tickets, purchased to visit families for Christmas, would molder in in-boxes.

Terry McAllister and Elizabeth O’Toole did not shut off their computers as John Campbell had; the overheated hum sounded to them like breathing, albeit the strained gasps of hospice-bed bellows. Before they left for Terry McAllister’s apartment in Georgetown, Elizabeth O’Toole asked Etta Hoffmann to come with them. Terry McAllister had told Elizabeth O’Toole not to bother, but Elizabeth O’Toole did not want to leave the other woman alone. Terry McAllister was right. Hoffmann stared at Elizabeth O’Toole as if her coworker were speaking Vietnamese. The Poet showed no more emotion at this final appeal than when being handed a cube of cake at an office birthday party.

While Terry McAllister and Elizabeth O’Toole prepared to leave, they heard the dull clack, clack, clack of Hoffmann’s robotic typing. Elizabeth O’Toole decided that Hoffmann’s lifeless, dogged work ethic reminded her of the lifeless, dogged attackers described in the reports that had flooded into the office. Maybe Hoffmann, already so much like Them—even this early, Them and They had become the terms of choice—was the perfect one to understand, process, and respond to Their threat. On the seventh day, inside Terry McAllister’s apartment, Elizabeth O’Toole used her phone, which clung to a single bar of signal, to text her cousin, a priest in Indianapolis, to confess her sins. She added that she and a lover, who was not her husband, were going to try to get out of Washington. Because she had little time and battery to spare, the text was rife with misspellings. Elizabeth O’Toole wasn’t watching when the phone died, so would never know if her confession had been sent or if it were one more unheard whimper at the end of the world. As she and Terry McAllister stepped from the blood-smeared foyer of the building onto a sidewalk scorched with gunpowder, with no plan other than to follow his hunch to “head north,” Elizabeth O’Toole saw her final message everywhere she looked, the letters like carrion birds daggering the November sky.

I parobalgy wont see yu agaon so Absovle me i yuo can dfrom where you are if it is legal8 bc I hae tried to make an act of contritiojn but I cant mreember all the owrds and isnt that the scareiest thign of all how lilttel I can remember alreyad like none of itever happened? lieka ll of the life we evre lived wsa all a dream?

The Living Dead George A. Romero, Daniel Kraus

'A horror landmark, a work of gory genius marked by all of Romero's trademark wit, humanity, and merciless social observation . . . the man who made the dead walk.' said Joe Hill, bestselling author of NOS4A2

Buy now