- Published: 14 September 2021

- ISBN: 9781529112276

- Imprint: Vintage

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 464

- RRP: $29.99

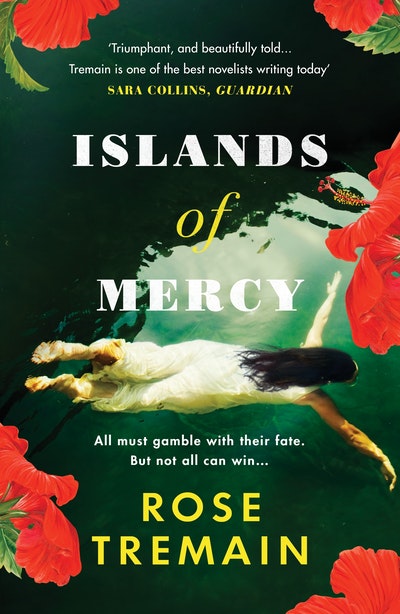

Islands of Mercy

Extract

Part One

THE RUBY NECKLACE

She came from Dublin.

In that crowded city, she had worked for a haberdasher and presided over the slow death of her mother, after which she’d discovered in herself an unexpected yearning to leave Ireland and see the world. Her name was Clorinda Morrissey and she was thirty-eight years old when she arrived in the English city of Bath. The year was 1865. She was not beautiful, but she had a smile of great sweetness and a soft voice that could soothe and calm the soul.

Clorinda knew that Bath was not exactly ‘the world’. But she had been told that it was built on seven hills, like Rome, and that it hosted ‘galas and illuminations’ in the spring and autumn seasons, and these things took on some splendour in her mind. It was also, she heard, a place where very many rich people assembled, to take the waters, or simply to take their leisure, and where the rich congregated, there was always money to be made.

Poorly lodged at first on Avon Street, at the lower end of the town, where the gutters were choked with refuse, among which dozens of pigs wandered in the daytime and at night lay down to sleep in their own comfortable filth, Clorinda Morrissey began her sojourn in Bath by working as a milliner’s assistant in the cold basement of a shop on Milsom Street. This work was punishing to the hands. Though she kept reminding herself that it afforded her a ‘living’, she soon came to feel that this living resembled nothing so much as a kind of ‘dying’ and it made her furious to think that she’d left Dublin only to find herself suffering from feelings of collapse and decline. She vowed to alter her lot as quickly as possible, before her spirit failed her.

The only article of value she possessed was a ruby necklace. It was an object of some beauty: twenty blood-red stones strung upon a delicate gold thread, with a golden clasp. It had come to Clorinda recently from her dead mother, who, in turn, had had it from her dead mother, and she, in monotonous rotation, from hers. For long and featureless years, this necklace had been passed from one place of safekeeping to another. It had hardly been worn by any of its owners, but rather had taken on the petrified status of an heirloom, kept in a satin-lined box, dipped in methylated spirits once in a while, to clean it and show its brilliance to the air. For long periods of time, it was forgotten completely, as though it didn’t exist at all.

Rumours that the great-grandmother had got it ‘by dishonourable means’ seeped down the generations, but these, if anything, only made each successive inheritor more keen to hang onto it. All of them believed that the ruby necklace would one day ‘find its true purpose’. But what that purpose might be, even if it was speculated upon, was never decided. The necklace remained hidden away in peculiar places: under floorboards, inside a broken longcase clock, in the secret compartment of an empty wall cupboard where bowls of hyacinth bulbs were nurtured through the winter darkness.

Now, however, Clorinda Morrissey, toiling over stiff bonnets and the fabrication of cloth flowers to attach to them, in her cold basement, made a vertiginous decision regarding the ruby necklace. She was going to sell it.

To the voice inside her which protested that she was betraying the status of the necklace as an heirloom, to be passed on to future generations, she replied that she had no children, so there was no ‘future generation’ to pass it on to. To the idea that, by moral right, she should leave it to one of her brother’s girls back in Dublin, she gave scarcely any consideration. These two nieces, Maire and Aisling, meant nothing at all to her. They struck her as dim, morose children, who probably did not even know of the existence of the necklace. And the rubies, she now saw uncommonly clearly, had no value whatsoever to anyone, until or unless that value could be realised. Surely, after all these silent generations had lived and died, it was time for someone to put them to use?

She took the necklace first to a pawnbroker. This elderly person applied a cup-shaped object to his eye and gazed at the rubies through it. Clorinda Morrissey, watching him with her sharp gaze, saw a tiny froth of saliva escape from his mouth and dribble down his chin. She deduced correctly from this that the man had at once understood that, among the dross of gilt, brass, glass, ivory and pewter habitually offered to him, here at last was a thing of uncommon beauty and value. He laid the cup aside, wiped his lips with a limp handkerchief, cleared his throat and made Clorinda an offer.

But it would not do. Mrs Morrissey was intent on changing her life. She knew that what was being proposed, although more than she could earn in six months at the milliner’s, was miserly. A violent hatred towards the cynical pawnbroker surged up in her breast, a loathing as red and heartless as the jewels themselves. She didn’t argue with the despicable man. She snatched up the necklace, replaced it in its box and prepared to walk out of the shop without another word. As she got to the door, she heard the pawnbroker call her back, raising his offer by a fraction, but she kept going.

The following day, she paid sixpence to borrow a fancy bonnet from the milliner, arranged her hair carefully beneath it, put on her best coat and clean shoes and marched into a high society jeweller’s on Camden Street. Her entrance into this shop set ringing a little melodic bell above the door, and she took this for a sign of welcome.

The money Clorinda Morrissey obtained for the rubies, paid in gold sovereigns, signed for on an embossed Bill of Sale with as much flourish as she was able to muster, put her into a trance of what she called ‘pure purpose’. She did not sleep. She sewed the sovereigns into the hem of a cambric petticoat. She chose to believe that her thirty-eight years of life had been lived in a kind of semi-darkness, but that now she would journey towards the light. And she knew exactly where she wanted that light to fall.

Further down Camden Street there was an empty shop premises. It had formerly been a funeral parlour which, Clorinda was told, had gone out of business ‘due to insufficient deaths in the city’. It was explained to her that although Bath had a very high population of sick and suffering people, these were mainly ‘imports to the town’ who came hoping to be cured by the healing waters and who were indeed cured – or else went back to their homes to die. Bath’s indigenous population was extremely long-lived. The steep hills around the city kept the people’s hearts beating strongly. The air they breathed – at least in the upper part of the city – was very pure, compared to London and many other cities. Entertainments of all kinds kept them from despair. Reasons for dying were comparatively few.

The funeral parlour, however, was large: a handsome office at the front, where examples of coffin design were still on display, bolted to the wall. At the back, two rooms, kept as cool as possible by an arrangement of iron pipes ventilating into a sunless back alley and once furnished with expensive fresh-cut flowers, had served as ‘viewing parlours’ for those bereaved relatives who could stomach the sight and stench of an embalmed corpse.

Mrs Morrissey walked back and forth between these two areas, arranged to accommodate the conventions of English burial. And she saw immediately how her Irish spirit could adapt them very satisfactorily to her need for what she liked to think of as her resurrection. She stood at the window facing Camden Street and watched the scores of beautifully attired people strolling past. Her mind returned to the ruby necklace. She half expected to see it, adorning the crumpled neck of some wealthy dowager, but then she reasoned that it wasn’t necessarily the kind of jewel to be worn in the daytime, but rather saved for one of these ‘gala evenings’ that had been allowed to acquire such splendour in her mind, but of which she had heard little since arriving in Bath. And anyway, the necklace was no longer itself. It was on the very precipice of becoming something else.

Once she’d signed her lease and engaged workmen to refit the premises, she wrote out a notice and attached it to the front door of the shop with milliner’s glue. It read: Opening soon in this place. Mrs Morrissey’s high class Tea Rooms.

What Clorinda Morrissey wanted from her enterprise was not only to make the kind of living that had nothing of the ‘dying’ about it, but also for herself to become known – a landmark, a magnet, a destination in her own right. Though she had had many friends in Dublin, it had always seemed to her that in the great life of the city she had had no importance whatsoever. She was invisible in her haberdasher’s shop.

In the taverns, where she could match the men, mug for mug of ale, nobody paid her any special attention. She’d had a suitor once, a carrot-headed boy who had walked with his head in the clouds and been run over by the night mail coach. Later, she had had a proposal from a Norwegian sailor and wondered for a while whether she might enjoy lying in arms so strong and foreign, so inured against the cold. But in the end, she’d decided against him. The carrot-headed boy had died with his face turned to the sky; the Norwegian would probably fall into the sea and drown. And it came to her then that she didn’t really want to live with a man – or at least not yet, not until she found someone whose gaze was steady and whose feet were planted firmly on the earth. She wanted to live for herself, to travel her own road. By the time she set sail for England, she’d reinvented herself as a widow, because widows survived far more cleverly in English society than spinsters – or so she’d been told.

And now she was going to have her name in gold script above the shop: Mrs Morrissey’s High Class Tea Rooms. The future was going to be perfumed with raspberry jam and freshly baked scones and fragrant lemon cake. With a dairyman on Carter Street, she placed a substantial twice-weekly order of Devon clotted cream.

Islands of Mercy Rose Tremain

An audacious novel about destiny and desire from the incomparable Rose Tremain

Buy now