- Published: 30 July 2024

- ISBN: 9781761344541

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 400

- RRP: $24.99

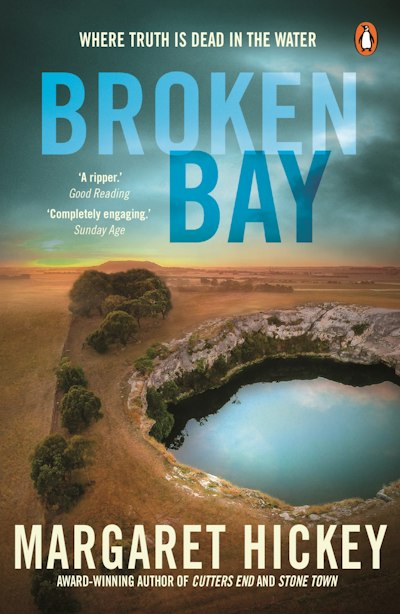

Broken Bay

Extract

‘This nutcase.’ Judy retrieved a newspaper from her back pocket and stabbed her finger at the photo on the front page. ‘Says here she was the female world record holder for deep cave diving.’

‘Rocks in her head.’

‘Well, it’s still a tragedy.’

‘You both dive,’ Georgia pointed out. ‘You’re divers.’

‘In the ocean. Not in some bloody pit in the ground.’

The family packed the nets away in silence. Above their heads, the painted red sign reading Sinclair Lobsters, finest in SA! hung like a speech bubble from a bad cartoon.

The old boat strove against the wind and rain until landmarks on the shore became visible. There was the old whaling factory, there was the Catholic church, there was the outline of Coles.

‘You all right now, love?’ Judy turned her attention to him.

Mark Ariti nodded, white knuckles tight on the rail, his back to the callous sea. After all the vomiting, he’d broken into a cold sweat, head thumping, dizzy with nausea. Concentrating on what the family was saying and doing had helped. A little.

‘Things will look up, Phil,’ Judy said to her husband. ‘Come summer, our fishing trips will be booked out!’

Phil looked at her, glum.

‘So, what happened?’ Georgia asked. ‘If that Mya person was so great at diving, how come she died?’

Her father looked at the deck almost angrily. ‘We don’t know how. What they’re saying on the radio is that when she didn’t resurface, other divers went down the sinkhole to look for her and saw that she’d gone through a squeeze. None of them were qualified enough to go through, so they’re waiting on experts to retrieve her body.’

Georgia frowned. ‘She can’t have been that good if she couldn’t make it back out.’

‘Oh, she’d have been good all right,’ Phil said, nodding at the sea as if it was agreeing with him. ‘But being good isn’t enough in cave diving. You have to be outstanding, and lucky. And stupid.’

The young teenager shrugged. Stepping into the cabin, she shut the door hard behind her.

‘There’ll be an inquiry,’ Judy mused. ‘More people in town.’

Phil shook his head and held his hand up to ward off a sharp ray of sunshine cutting through the grey. ‘Should just leave the body there and cover the hole up. No point endangering others.’

‘The family will want to bury her.’ Judy rolled up the newspaper and stuck it in her bag. ‘If it was Georgia down there, I’d want her back.’

‘Georgia would never be that stupid,’ Phil said, although on that note he looked doubtful.

‘We should get into the cave diving industry,’ Georgia called from inside the cabin, her little face poking through the window. ‘Forget about the daytrippers and the fishing charters. We could cater to the divers of the world.’

‘Not on your nelly,’ her dad shouted back. ‘Lobsters at least have got a bit of sense.’

Judy gave Mark a gentle pat on the shoulder, handed him some water. ‘You’re looking green again, love. Take some small sips.’

‘Perfect day for it,’ Phil commented. ‘Five knots, sea’s not quite half a metre, count yourself lucky. Cold, choppy, but yesterday the swell was up to three metres.’

God, I hate the ocean, Mark thought.

‘Still,’ Judy said, chirpy, ‘you caught a nice flathead, Mark. I’ll gut it for you so you can have it for dinner.’

Mark only liked fish that was battered and covered in tartare sauce. He didn’t want the fish, tried to reject the offer with a weak wave.

‘Squeeze of lemon, pinch of pepper and you’ll have the best meal of your life.’ Judy hauled the fish out of an esky and slapped it onto a bench in the centre of the deck. ‘Bit of lettuce on the side, slice of tomato and bob’s your uncle.’ She slid a knife into the belly of the fish and its guts fell out. ‘You’ve had a bit of sea sickness,’ she continued, her skilful knife moving through the flesh, ‘but it’s been a good day, hasn’t it? You’re one of our first charter customers – we’ll want a true assessment, the good and the bad.’

A small piece of curled innards fell on Mark’s shoe. He croaked something.

‘What’s that, love?’

‘I said, it’s—’

The boat caught the bottom of a wave, dipped low and then heaved up again. Mark turned, leaned over the side and retched. Long strings of saliva blew about in the wind like spiderwebs. He burped, then spewed again. After a wretched minute, he slumped back onto the bench, wiping his hand across his mouth. ‘It’s probably the best day of my life.’

What else could he say? That he hated every moment, hated his sister Prue for giving him the voucher for an ocean fishing trip in Broken Bay, hated the unpredictable weather, hated the diesel fumes and the relentless waves?

Judy gave a short laugh. ‘You’ll survive,’ she said. ‘I remember when I first went out with Phil years ago – thought I was dying when we left the heads.’

Mark peered up at the woman as he tried a sip of water. Like her husband, Judy’s face was a synoptic weather chart, etched hard with swirled wrinkles and dark freckles, deep lines rushing from chin to neck in a strong current. Clear blue eyes, the exact colour of the sea, and a wiry body. But while Phil had the same weathered look, they differed greatly in build. He was a burly giant – a sea captain character from a children’s book. He should have a pipe out the side of his mouth and a parrot on his shoulder, Mark thought. Only the bird would be blown to Antarctica in half a second.

At the start of the voyage – because that’s how Mark liked to think of it, a voyage – Phil had told him not to fight the rocking of the boat. Stand legs apart, move with it, like it’s a horse. And only now, returning into the bay, was Mark game to try it, getting up from the bench. The waves were smaller, choppy, and foam smacked hard into his face, but his new stance made him feel less weak. For the second time in three hours, he took stock of the empty cray nets, sodden ropes and faded sign.

‘Not a good season?’ Mark asked.

‘Something’s off with the crays.’ Phil shrugged. ‘Water’s too warm or too hot – can’t tell these days, probably both.’

‘Nowadays trout’s rare in the river where I’m from. Used to catch them easy. It’s the droughts, or the floods.’

‘Or the fires,’ Judy piped up.

The three grew silent. They knew what it was. Felt the slow dread each time the temperature edged into the thirties in winter, or when creeks overflowed in February. There had been two mass fish kills in the past three years in Mark’s hometown of Booralama, the sight of them a horror: massive cods, floating dead on the surface, others panting in the shallows.

‘From up north, aren’t you?’ Phil asked, and Mark nodded. ‘Nice country, but I couldn’t live there. Start to feel antsy if I’m more than three days away from it.’ The big man threw his arm out towards the ocean.

‘I’m more of a river man,’ Mark said.

‘You don’t say,’ Judy quipped, and they all smiled.

Judy slowed the boat and steered them into the mouth of the river where the jetties were now lined with old fishing vessels and tinnies and the odd yacht. Golden light on the water shimmered, peaceful. Deceitful.

‘Come with us for a beer,’ Phil suggested. ‘You’re one of our first customers on Sinclair Tours and we owe you one after this trip.’

Mark needed a Panadol and a lie-down, but the beaming couple looked so pleased by the idea that he agreed. They arranged to meet in an hour at the Royal.

After stumbling weak-kneed onto the jetty and then into his car, Mark drove back to the Hibernian Motel, his home for the next two nights. The streets were wide and bare, bluestone gutters gleamed hard in the afternoon light and, out of all the shops, only Coles and the bottle-o were open. Broken Bay was a small town, tough, full of ugly buildings and squat houses. Perhaps it was on the verge of discovery by sea changers, but the wave of city cash seemed a while off yet. An old whaling station and Catholic church on the main street were the only grand structures, and what that signified required a clearer head. The body and the blood.

He pulled into the car park of the motel and waved to Ian Bickon, the mule-faced owner. Ian was hosing a dying camellia with serious intent, staring into the dirt, the stream at full pressure. Was Ian waterboarding the plant?

Once inside his room, Mark pulled off his shoes and lay on one of the single beds, looking up at the salmon-coloured ceiling. It reminded him of the curled piece of guts on the boat and, with some relief, he realised he’d forgotten to bring the flathead home.

It was 5.30 pm. A stiff breeze blew through the open window, the lace curtains rising up in a bad burlesque. An arm’s length away, the second bed lay frigid and cold. Ian had placed him in a room with two singles rather than a queen because, he explained, Mark had come to Broken Bay on his own. Mark had been tempted to tell Ian about Rose, maybe even show him a photo, boast to Ian that his beautiful girlfriend was a doctor. But then he’d have to admit the reality of their looming split.

Mark reached for the bedside lamp and flicked it on. It was all decided – after months of deliberation and lengthy discussion, Rose was off to Tanzania for a year working as a medic in a town south of Dar es Salaam. Visa sorted and flights booked, Rose was due to leave in a week. She’d asked him to go with her, and he had said no. A no-man’s-land had expanded between them, memories curdling like photos in the heat. Mark had his boys, he’d built a life in his hometown, had his friends, the house. Rose knew all that, Rose liked all that – but still Rose was going. She held a dim view of long-distance relationships. Dim. As someone who’d previously lived in Broome while her ex-partner was in Hobart, she said she knew how it was likely to go. Mark got the message. He could have explained to mule-faced Ian that perhaps he and Rose weren’t meant to make it. She didn’t have children and, while she liked his, clearly preferred it when his two sons were not around. She found Booralama dull on weekends – it mostly was – and she liked to go to yoga retreats and camp at music festivals; he did not. She was funny and smart and good-looking . . . but he and Rose were over. She was already talking about a move to Kenya after Tanzania.

Mark closed his eyes and thought about the women he knew. If he really pressed Ian, held him down and forced him to listen to his relationship woes, he might have told the man about his ex-wife, Kelly, mother of his two boys, and how they had built an amicable relationship. Or even about his friend and colleague Jagdeep, steadfast in loyalty and grit. If after that Ian still showed signs of life, Mark could tell tales about his sister, Prue, his friend Donna and his mother, Helen, dead now for over a year.

But Ian wouldn’t care. And who could blame him? Ian only liked to inflict torture on plants. And good on him. Good on you, Ian.

Mark had a shower, then stood side-on in front of the mirror while he towelled himself, noting the puff of grey chest hair and gut. A whole lifestyle away from a six-pack, but running three times a week helped to stave off elastic waists and man boobs. He moved to face the mirror, sucked in his stomach and wondered at the years since he was a teenager, when stripping off his T-shirt at the local pool had been a kind of joy.

Mark flicked on the small TV and caught the tail end of a story about the cave diver Mya Rennik. Local farmer Frank Doyle was meeting with Australian cave diving experts to discuss the prospect of diving there after Mya failed to surface from the sinkhole on his property. ‘With increased safety measures, the ever-growing sport could offer substantial tourism funding for the area, now that the lobster and dairy industries are in freefall,’ the young journalist concluded, sober faced.

Mark’s phone rang: Prue.

‘How was your time with Sinclair Tours?’ she asked.

‘Like The Poseidon Adventure.’ Mark began putting on his clothes. ‘Only worse.’

‘That bad?’

Once he’d done up his shirt buttons with one hand, he sat on the bed to put on his shoes. ‘Prue, you know how much I hate the sea.’

His sister put her hand over the phone, calling out to someone in the background. ‘Yes, yes,’ she said. ‘But really, you’ve only been in a boat on the ocean, what – twice, three times? Twice in a tinny with Dad and me, and the other on a boat off Hamilton Island. You’ve got to give these things a chance! Be more adventurous!’

Mark considered: the boat off Hamilton Island with his friend Dennis was on relatively calm waters and the main reason for his vomiting was the bourbon and prawns. The tinny, though, that was a distant memory, infused with a strange anxiety. ‘Where were we in that tinny?’ he asked.

‘Port Fairy in Victoria one time and the other, Broken Bay! Where you are now. Don’t you remember? It was just you and Dad. You went down there for a boys’ weekend.’

‘I was a kid, Prue. I can barely remember.’

‘You both had the best time!’

Mark made a doubtful humph.

His sister began telling him about all the times she’d been sailing with her husband in English Bay, Vancouver. How they’d take their three sons and go fishing for salmon and halibut and how sometimes they’d dock their boat at some bay, crack open some nice beers and—

‘What’s it like being rich, Prue?’ Mark asked, staring at the painting of leaping dolphins on the wall opposite. One dolphin was smiling and a ray of sunshine bore down on the beaming creature. ‘Like, really rich?’

‘It’s good.’ Prue was always honest. ‘Less to worry about. Rich people don’t stoop, ever noticed that? You should bring the boys here for a holiday.’

‘Yeah.’ He should.

‘And what’s your accommodation like? You book somewhere nice?’

‘Sheer luxury.’

‘How’s Rose?’

‘She’s great, just great.’

They chatted for a few more minutes; Prue asking the questions, Mark answering, before he checked his watch and said he had to go.

It was close to six o’clock. Outside, the wind made a high keening sound and somewhere nearby a door banged on its hinges. So he and his father came to Broken Bay on holiday when he was a kid. Why? Mostly they went to Queensland to visit cousins, long trips in a hot car with his parents smoking the entire time. Why had they come on a father–son holiday to the far east of South Australia? His parents hated the cold. Vague memories of grey water and a brittle wind hovered in his mind. The memory lingered, then died.

Broken Bay Margaret Hickey

From the author of the bestselling and award-winning Cutters End and Stone Town, a captivating new crime novel featuring Detective Mark Ariti.

Buy now