Peter Greste reflects on the dangers associated with seeking the truth.

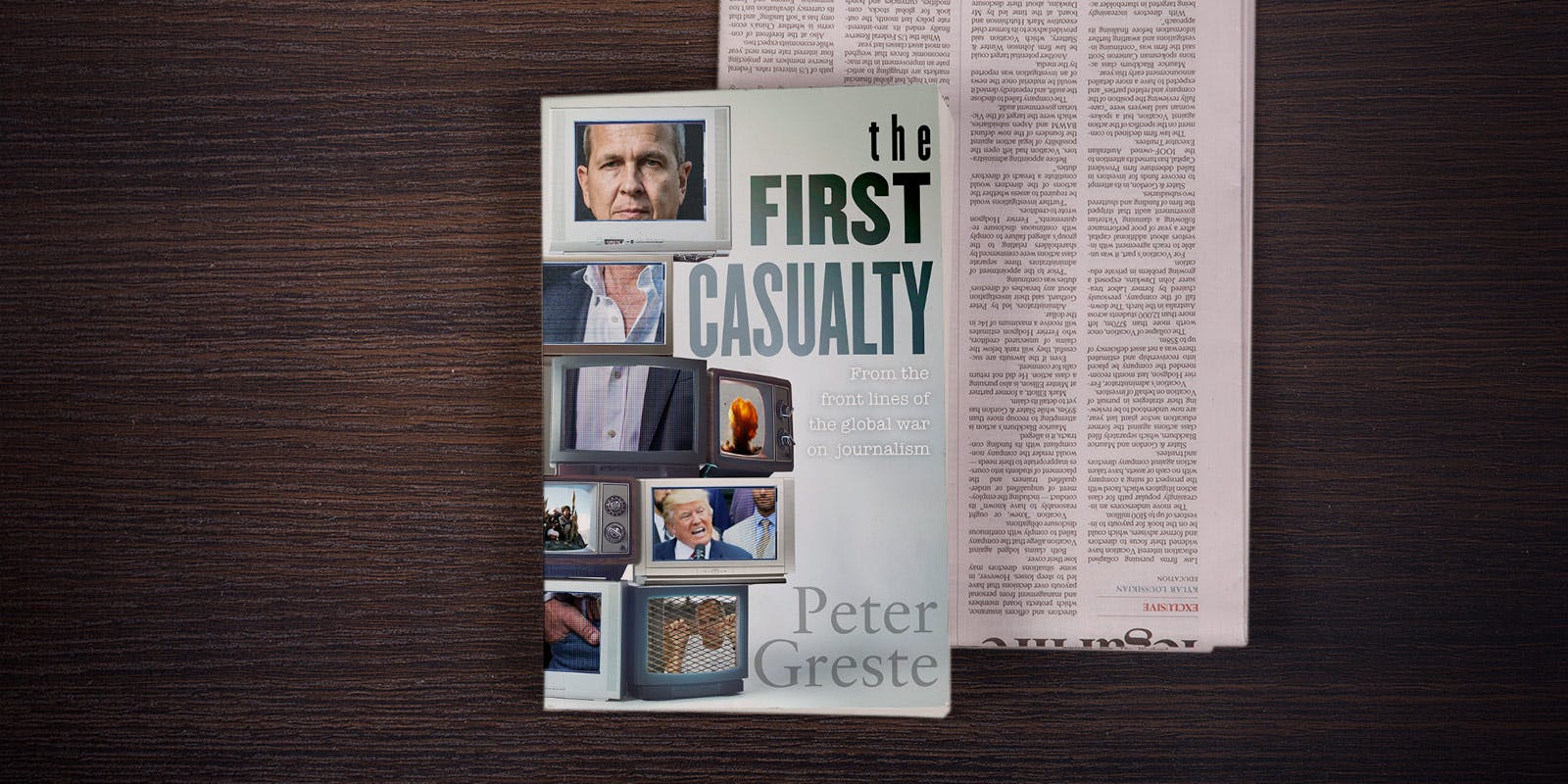

During Australian journalist Peter Greste’s career, the landscape changed dramatically for those reporting on the world’s hotspots. Where foreign correspondents were once seen as valuable witnesses to conflict, and useful tools in the communications war, they have now become part of the battlefield – scapegoats and targets in their own right. The First Casualty is Peter Greste’s account of two decades reporting from the front line in the world’s most dangerous countries. And a reflection on how the war on journalism has spread from the battlefields of the Middle East to the governments of the West.

In Kabul during the 1990s, radio reigned supreme as a news source, and the BBC’s Pashto and Farsi broadcasts were among the most credible and popular. While working for the BBC in Kabul during this time, Greste says fair and balanced coverage of all sides of the Afghan Civil War was not only a matter of upholding the legitimacy of the BBC brand and professional ethics, but one of survival. ‘For me, as a newly arrived correspondent, it was crucial to establish contacts with all the rival groups, regardless of their politics or ethnic make-up,’ he says. ‘Seeing [dominant political group] Jamiat [-e Islami] officials was relatively easy – we lived in territory they controlled – but we also needed to build a relationship with the opposition, which was a much riskier proposition.’

In the mid-1990s, there was a new, little-known player starting to exert some prominence in the war. In the passage below Greste recounts a trip out of the capital to meet with a militia group that several years later would become an international household name.

Back in 1995, the Taliban was just another militia in an already overcrowded and over-armed landscape. It seemed unlikely that it would ever be a significant player, but its members were a little different: they refused to align themselves with any other group.

They also had a strong story to tell about how they had formed. Although there was some uncertainty, it is now widely accepted that the movement came out of madrasahs (religious schools) in the refugee camps of neighbouring Pakistan as a reaction to the corruption and lawlessness of the factions that had ground down the country for years. ‘Taliban’ literally means ‘student’, and the Qur’an was the movement’s inspiration. In the absence of any functioning legal system, like other mujahedin factions it used sharia law as its organising principle, except that Taliban took their religious devotion and piety to a fanatical level.

The Taliban’s own foundation myth tells how Mullah Omar first mobilised his followers in the spring of 1994 when he learned that the local governor in the southern district of Singesar had abducted and systematically raped two teenage girls. Mullah Omar organised a relatively small force of thirty Taliban and freed the girls before executing the governor. Some weeks later, two militia commanders in the Mullah’s home town of Kandahar killed civilians while fighting for their right to sodomise a young boy. Once more Mullah Omar moved in. He freed the boy and executed the two commanders, but this time he stayed.

Over the following months supporters flooded in from Pakistan, and the Taliban quickly took control of the nearest border crossing, at Spin Boldak. Neighbouring districts fell as locals fed up with the anarchy of the warlords joined the movement, and the new force began advancing north towards Kabul, declaring that its ultimate goal was to destroy all the mujahedin factions, restore law and order, and establish an Islamic state based on sharia law across all Afghanistan.

These goals were noble enough, but there were other agendas. Some analysts believe the Taliban was a creation of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Certainly, if the ISI didn’t invent the movement it took advantage of the opportunity that Mullah Omar presented, supporting him with money, arms, ammunition and a near-endless supply of recruits.1 Pakistan saw the Taliban as a way of exerting control over its neighbour, and opening up trade routes to Central Asian countries such as Uzbekistan.

So when Maidan Shahr, on the south-western approach to Kabul, fell to the Taliban after a brief but fierce battle with Hekmatyar’s troops, it became clear that they were a significant force in their own right and we needed to go and see them. Maidan Shahr sits at the southern end of a long valley. Whoever controls the town controls all the traffic into Kabul’s southern flank, about 30 kilometres away.

Countless tanks had broken up the road out of the capital, hollowing out vast potholes, and as we drove along it, our Land Rover rose and fell like a ship in a heavy swell, disappearing completely in the troughs before cresting and then vanishing once more. Finally the road flattened out as we rounded a bend at the head of a broad, U-shaped valley. The road was brown, barren and dead straight, with government trenches and tanks in defensive positions at our end, and the Taliban trenches just visible at the opposite end about 4 kilometres away.

On the day we arrived there was no shooting – local villagers told us it had been quiet for hours – and we watched as a few civilian trucks bounced their way across the battlefield. Once they’d made it safely through, I turned to Salahuddin and Hajji with a question in my eyes.

Without answering, Hajji shrugged and started the engine.

As we approached the Taliban end, I struggled to control the sweat that had beaded on my forehead despite the winter chill. I could see black turbans rising above the Kalashnikov barrels that poked through the sandbagged barrier, and couldn’t help but think of the stories we’d heard of the ruthless executions of anybody the Taliban disagreed with. It was always risky approaching a line without prior warning, but in capturing Maidan Shahr, the Taliban had just won a significant victory, and we hoped they’d be feeling confident and relaxed.

We stopped at the checkpoint, safely out of range of the government trenches, and the Taliban commander approached our car. His weathered Pashtun eyes widened as soon as he saw me a white man on an Afghan battlefield – and he broke into a huge grin.

‘BBC?’ he asked, glancing up at the flag hanging from the mast at the back of the car. ‘Welcome, welcome.’