- Published: 4 June 2019

- ISBN: 9780143784562

- Imprint: Michael Joseph

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 368

- RRP: $32.99

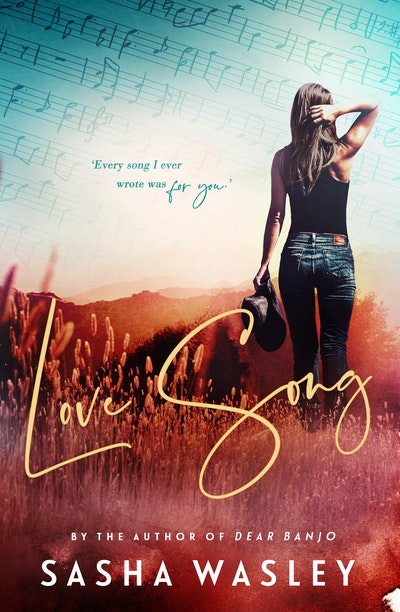

Love Song

Extract

Chapter 1

Beth leaned against a fence post and looked across the red dirt paddock, puffing. The run to the Paterson Downs gate and back was only 3 kilometres, but it was the best running trail at the station. The straightest, flattest, least dusty trail. No cow pats. And even a short run was better than no run at all.

She turned to observe the house. Hopelessly outdated. How many times had she subtly suggested renovation to her father or Willow? Barry barely seemed to listen, while Willow always gave her the look that meant ‘Are you insane?’ Willow adored the old homestead and seemed blind to how unfashionable it was. But all it would take was a little bit of rendering on the mission-brown brickwork – perhaps a dark grey – and a classy stone portico right over the top of that ridiculous arch . . .

What was the point in envisioning renovations to the Paterson Downs homestead? Even if Beth managed to talk her father around, Willow would just veto the idea. Beth caught sight of her mother’s dragon-embellished doorbell swinging gently in the morning breeze and her heart softened. There were some things even she wouldn’t change about the old place.

Willow came out through the front door and checked the boots that lived on the doorstep for snakes or toads. She caught sight of Beth.

‘Good run?’

Beth approached, nodding. ‘A bit short but it’s too hot to run now anyway. I slept in.’

‘It’s only eight,’ said Willow. ‘And it’s a Sunday. I think you’re permitted a sleep-in after dealing with Mount Clair’s diseased all week. By some people’s standards, this is revoltingly early.’

‘But by yours, it’s late in the day,’ Beth said with a smile. ‘What are you up to this morning?’

‘Tom and I are heading over to Quintilla. The goats have arrived!’ Willow’s dark eyes sparkled.

‘Oh, that’s exciting! Are any of them coming to Patersons?’

‘Not yet. These guys were raised organic so they’re certified already. We’ll keep them at Quintilla until Patersons is fully certified, so they don’t lose their organic standing.’

Tom stepped outside behind Willow, his blond hair flattened where his hat had been sitting. ‘You been jogging, Beth? Crazy woman.’

Beth wiped her forehead with her arm. ‘I don’t have hard manual labour to keep me fit like you two do. I have to do something.’

Willow laughed. ‘That’s not why you jog.’

Beth looked at her in surprise. ‘Why else would I do it?’

Willow hesitated. ‘I don’t know. I figured it was a stress release for you.’ Beth raised her eyebrows. ‘I mean, no-one needs to run for over an hour every morning and night to stay fit, do they?’

It did sound fanatical, put like that. Beth’s cheeks warmed. ‘Yeah, I guess it’s a good way to wind down.’

Tom nudged Willow. ‘Goats wait for no man – or woman.’

‘Coming!’ Willow approached Beth for a hug. ‘In case you’re gone when I get back.’

‘I’m all sweaty,’ Beth protested.

‘Yeah, that’s gross – don’t get your sweat all over my sweat.’ Willow grinned and took off after Tom.

Beth watched as they climbed into a farm vehicle, discussing their new livestock in animated tones. Just over two months pregnant, Willow had no baby bump to speak of so far, but soon enough she would have to tell the world. Willow would be so embarrassed by all the attention she would get – and Tom would glory in it. Beth smiled as warmth stole over her heart. Tom Forrest was the only man she considered good enough for her precious sister – the only man she really trusted to value Willow properly. And never to hurt her.

As for Free’s boyfriend, Finn – well, the jury was still out for Beth. He seemed to adore Free like she should be adored, and he’d certainly had an anchoring effect on the youngest Paterson sister. For the first time in her adult life, Free seemed happy to stay in one place for more than a few months at a time. Finn had been around for almost a year now, but Beth would reserve judgement until he’d lasted a couple more. Beth pictured Free’s sunny, open face and soft golden hair and was hit with a stab of love so fierce it almost took her breath away. If he hurt Free, Constable Finn Kelly wouldn’t want to face Beth’s wrath.

She waved Tom and Willow off and went inside for a drink. Barry was in front of the television, sound down, frowning over his planting diary.

‘Morning, sweetheart. You been jogging out there? Bloody hot. You’ll get heat stroke if you don’t watch out.’

‘I’m fine, Dad. I’m used to it.’

‘Hmm.’ He focused back on his diary as she went for the water jug in the fridge. ‘You want a cuppa, Bethie?’

‘Not yet. I’ll have a shower first. Have you eaten? Do you fancy a cooked breakfast?’

Barry’s face lit up. ‘Bacon and eggs?’

‘Dad.’ She didn’t even have to finish. He raised his hand in defeat. ‘Poached eggs on toast,’ she said.

‘Sounds beautiful, sweetheart. Don’t tell your sister this, but you’ll always be the best bloody cook in Mount Clair.’

Beth was unable to help a smile. ‘Taught by Mum – the master. But you only think I’m better than Willow because I cook with meat.’

He chuckled. ‘Nah, you’ve got magic in your fingers. Go and have your shower and I’ll get the kettle on.’

Beth enjoyed the slow morning at the station. She nattered and joked with her father, and found some clean washing to fold in the laundry, knowing how hard Willow and Tom worked. Coming back to her childhood home never failed to remind her to live life at a gentler pace – or at least to try.

On the drive back to town in the afternoon, Beth thought about the next couple of days. They already looked crazy. She had appointments at the clinic until six on Monday and she still had to ask Paul or Carolyn if they could take any of her late appointments on Tuesday afternoon, since the Madjinbarra stakeholders had called a special meeting at five. Then she had a networking function at seven. She hoped there would be food there, because at that rate, she’d be lucky to squeeze in dinner. She had to get her own tests booked, too: a mammogram and a cervical screening. She’d never had an abnormal result but it was better to be vigilant, with her family history.

Her mind wandered back to the stakeholder meeting. She wasn’t sure why the meeting had been called – it wasn’t on the usual schedule. Her first thought was funding. Most extraordinary meetings were about funding problems, in Beth’s experience. Things were always changing in the government department that funded her role as Madjinbarra’s fly-in doctor, and she’d seen whole programs scrapped in the blink of an eye. Beth hoped this wouldn’t be the fate of the Madjinbarra program. They needed the medical visits, and she treasured her regular treks out there to see the members of the remote community. The work got her out of town for a few days every month and she’d connected with many of the people there, making a difference to their health. Her mind settled on Pearl, the big-eyed toddler with cerebral palsy, and her older sister, Jill. Beth was particularly fond of those two. Her warm thoughts clouded over for a moment as she contemplated Pearl. If only she lived in Mount Clair. The child needed more care than she could get out in the tiny town.

She would discuss the matter with Mary Wirra next time she saw her. As the girls’ guardian and a community elder, Mary was sure to want to explore options for Pearl’s wellbeing.

Beth was already exhausted when she headed to the Madjinbarra meeting at the Department of Communities office on Tuesday. She’d been called out to the hospital the night before when an unexpected rush in Emergency left them short on doctors. She hadn’t gone to bed until two in the morning and was up at six to get ready for work.

Maybe I’ll pass on the networking function later . . . But she hated missing any opportunity to build her business and connect with the movers and shakers of Mount Clair. Beth sighed as she pulled the Beast into the diagonal street parking outside the department office. Something would have to give, and the chamber of commerce function was the most dispensable activity in her day. She hadn’t been for a run, either, she recalled with a pang.

The big office with its worn carpet was full of people, and Beth got a shock when she recognised Mary Wirra, as well as Harvey Early. They were the most senior members of the Madjinbarra community, but it wasn’t often that they would come all this way just for a meeting. It must be serious. Mary caught sight of her and waved, so Beth joined them, kissing Mary’s cheek in greeting.

‘Hi, Mary, Harvey. What’s going on?’

Mary grimaced. ‘It’s bullshit, Doc. Gargantua wants to put in a mine camp.’

Beth understood in an instant. Mining conglomerate Gargantua held a lease close to the tiny town. The Madjinbarra community had been living under the threat of Gargantua calling in its rights for decades.

‘Oh, no,’ she said.

‘We already said no to them putting the workers’ camp into Madji,’ Harvey told her. ‘They’ve been going on and on, saying they’ll bring money and work to the community.’

‘And other things,’ Mary muttered.

‘We told them no way,’ Harvey went on. ‘Now they reckon they’ll build the workers’ camp at the mine, instead. Billy and me drove out there the other day to check how far it was. Didn’t even take us an hour to get there from Madji.’

Beth shook her head. ‘That’s too close.’

‘We built the camp at Madjinbarra forty years ago to get away from town life.’ Mary’s voice shook with emotion. ‘We don’t want our young folk getting into grog and trouble.’

Beth squeezed Mary’s hand, wishing there were something she could say to reassure the woman. She wondered why she had been called in to this meeting – after all, it wasn’t as though Beth would have any say in what happened. She glanced around and spotted Lloyd Rendall, a local solicitor, as well as some suits who must be from Gargantua. There were people she knew from the department, too, and a few other unfamiliar faces – thirty or more people in all.

‘Have you got legal representation?’ she asked.

‘Not yet,’ said Mary.

‘This is just the start,’ said Harvey. ‘You watch. They’ve called us in to make us see how small we are compared to all their executives and lawyers.’

Beth’s heart sank further. He was probably right.

‘We’ve got some good people though.’ Mary tried to rally Harvey. ‘Doc, we can rely on you to support us.’

‘Of course.’

Mary beamed at her. ‘And my nephew. He’s famous. He’s coming this arvo, too. He’ll stick up for us.’

Lloyd called everyone to attention and invited them to take a seat in the large meeting room, where chairs had been set up for the purpose. He took his place at the front of the room, clad in a well-cut suit. He was dressed to impress today. Normally Lloyd wore chinos and short-sleeved button-down shirts that strained over his slight beer gut. Gargantua would have to be one of his most valuable clients ever, Beth thought. He’d probably been seconded by the Gargantua legal team as a local face.

Lloyd nodded his greying head once or twice and thanked everyone for coming. ‘I’m a neutral party for the purposes of this evening’s meeting,’ he said. ‘I’ll simply be acting as a think-tank facilitator.’

More like a shark tank. Beth was vaguely aware of more people arriving, taking seats behind her while Lloyd introduced the team from Gargantua and the Madjinbarra elders. Clearly, this matter was polarising the community.

‘As you’d all know, we’re here to talk about the mining operation that’s proposed to open near the Madjinbarra remote community. When the mine is approved by the Mining Department, Gargantua employees will need a workers’ camp, but representatives of the Madjinbarra community have a few concerns about the matter. Gargantua’s position is that they can bring much-needed improvements to Madjinbarra – employment, business, amenities, and so on. I’m sure you’d all know that what’s in place out at Madjinbarra is pretty substandard. The couple of hundred people who live there have electricity, of course, and water. But it’s water drawn from a bore, and there’s very little phone or internet signal out there – sketchy satellite coverage at best. There’s a small co-operative where they sell mostly packaged staples; a run-down, under-resourced school; and a health clinic staffed once a month by a FIFO doctor.’ Lloyd paused and looked around. ‘Not what you’d call a thriving metropolis.’

Beth glowered. This was so unfair. Yes, the place was a little rough – when Beth visited it was like being in a different country – but she understood precisely why they valued it. It had been an oasis of calm for its inhabitants for generations. The children there were schooled by a devoted team of teachers – including locals who had been specially trained. Some of the kids had never even been to a big town. The community took in and rehabilitated the occasional outsider – people of Aboriginal heritage who were struggling with issues stemming from ongoing cultural trauma. Beth always came away from her monthly visit buzzing and re-energised, her faith in humanity restored.

‘The point of contention, as I understand it,’ Lloyd went on, ‘is the wet mess – the pub. A workers’ camp needs a pub, or you’re going to struggle to attract workers. But Madjinbarra’s elders claim that it’s been a dry community – alcohol free – for around . . .’ He checked his notes. ‘Fifteen years. And they’re a little concerned that a wet mess close by might cause problems in the town. Now, I think it would be advantageous at this point to hear from a few of the people involved.’

Lloyd called up a Gargantua executive first. The guy talked about the rich resources that had been identified through exploratory work and the potential fiscal benefits to the Madjinbarra community. He took care to remind everyone that Gargantua would not be infringing on Aboriginal land – the location of the proposed mine was just outside the native title on which Madjinbarra sat. He used all the right words: ‘community partnership’, ‘engagement’, ‘financial empowerment’. Beth sighed inwardly. This was going to be an uphill battle.

Harvey got up to speak next and he didn’t pull any punches. He said quite bluntly that the community wasn’t interested in Gargantua’s fiscal benefits and wanted to stay as it was. Beth cheered him privately, but her objective side knew he wasn’t as convincing as the Gargantua bloke – not to the decision-makers.

‘There have been some concerns raised about the problem of health care out at the community,’ Lloyd said when he reclaimed the speaker’s position. ‘Dr Paterson, you undertake regular visits to the community through the Remote Health program. I believe you have concerns that some residents at Madjinbarra cannot obtain the care they require while they’re so far from medical facilities, is that right?’

Beth went cold. Suddenly she knew why she had been invited. At the last chamber of commerce networking event, she’d been chatting to Lloyd. He had asked her about her role providing care out in the community. Unaware that Gargantua was sniffing around, she’d said it was rewarding, but confessed she was worried about a child who needed more care than she could get out at the community.

Beth saw Harvey look at her in shock and she stood, composing her features. ‘That’s incorrect. The Remote Health program is working extremely well for the Madjinbarra community.’

Lloyd frowned. ‘I understood there were members of the population out there who require more specialist care than a GP can provide through monthly visits. A child with a congenital condition, wasn’t it?’

‘Not quite, Mr Rendall. There is a child with cerebral palsy. From time to time, she will need specialist care. However, her family are giving her excellent care and she has all the equipment she needs, for her developmental stage.’

‘And the others? I’m aware there are a couple of older adults with diabetes, heart conditions; a recovering cancer patient. None of them require more than a monthly fly-in GP visit, even with such serious health conditions?’ Lloyd held her gaze, his face impassive.

Jerk. He’d done his homework. Neutral facilitator, my arse. He was here solely for Gargantua.

‘It’s not up to me to make that call,’ she said, watching him steadily. ‘The Remote Health working group has investigated thoroughly and deems a monthly GP visit to the community appropriate, in addition to the Madjinbarra clinicians, of course – a very competent nurse and an Aboriginal health officer.’

There was a noise behind her – someone else standing up. ‘Excuse me, Lloyd,’ came Mary’s voice. Beth sat, grateful to be out of the firing line. ‘My nephew’s come to Mount Clair to put his voice behind our community. He’s well-known all round Australia, and the TV and radios are pretty interested in what he’s got to say. He’s here tonight and has a few things to tell you fellas from Gargantua.’

Lloyd’s eyes flickered across the room and settled somewhere behind her – presumably on this nephew of Mary’s. Beth had a little moment of satisfaction, watching discomfort creep over Lloyd’s face. He even cast a hasty look at the Gargantua blokes. This has got to be good. Beth turned to check out the nephew herself, wondering who could be important enough to unsettle poker-faced Lloyd Rendall.

Oh, hell.

Love Song Sasha Wasley

The heart-warming new rural romance novel from the acclaimed author of Dear Banjo and True Blue.

Buy now